The re-enchanted canon: ten paintings to understand the return of classicism in 2026 and beyond

In 2026, pictorial classicism has returned —not as an archaeological citation but as a living repertoire that restores compass, proportion, and myth to the eye fatigued by the screen. In artists' studios, museums, and social media, ancient vocabularies reappear —friezes of idealized bodies, sacred triangles, serene horizons— which are reinterpreted with today's questions: identity, community, planet. This essay explores ten paintings canons (and their symbolic radiation) to show why classicism matters to us again. In each work, we unravel hidden symbols —numbers, gods, constellations, mystical geometries— and recount anecdotes, contexts, and legacies that re-enchant the contemporary gaze.

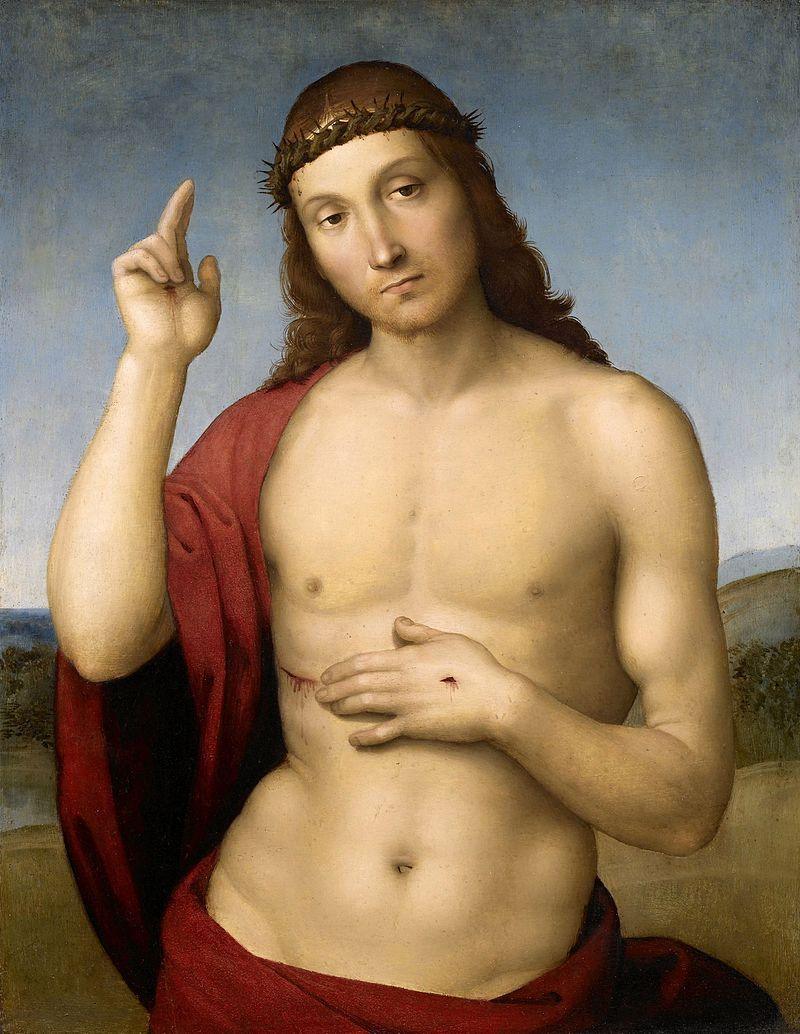

1) The School of Athens, Raphael (1509–1511)

Raphael orchestrates an imaginary temple where thought becomes a process. The central axis —Plato pointing upwards, Aristotle holding with his palm— articulates two cosmic vectors: the celestial (fire/air) and the terrestrial (water/earth). Plato's raised finger gesture is a solar hieroglyph; Aristotle's horizontal palm, a lunar seal that tames the light. The feigned architecture cites the Pantheon and, with it, the idea of a domed universe. The helmets, tablets, and compasses carried by some wise men —Pythagoras, Euclid— are not mere attributes: they are ritual instruments of a religion of measurement.

The composition distributes philosophers in constellations. On the left, Pythagoras writes proportions alongside a young man holding a slate: a small Masonic epiphany about the music of the spheres. On the right, Euclid traces with a compass —hermetic symbol of creation— a figure reminiscent of the hexagram, a union of opposites. Heraclitus himself, with features of Michelangelo, introduces tragic destiny into a scene of harmony. Everything is secretly numbered: twelve major groupings like the months of the year, four arches like seasons, a circle/triangle/rectangle that repeats on the marble floors as a mandala of thought.

Anecdotally, Raphael self-portraits as one of the observers on the margin. This subtle presence celebrates the Renaissance idea of the painter-philosopher. In 2026, the work is re-read as a manifesto: classical clarity does not exclude plurality; geometry does not oppress, it guides. The “hall of knowledge” becomes a curatorial ideal again: museums that diagram dialogues, schools that put beauty at the service of intellect.

Buy an oil reproduction of The School of Athens (Raphael) at KUADROS

2) The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David (1784)

Three stone arches, three brothers, three swords: the Pythagorean triad governs the design. David turns morality into architecture: the men, rigid and geometric (straight lines, tense arms), contrast with the women, curvilinear and subdued (wavy lines). The solar reason confronts the lunar pathos. The father, in the center, is a secular Pontiff: he raises the weapons as if they were relics. The scene seems to take place in a lodge: the invisible compass of the composition triangulates oath, duty, and sacrifice.

Numerology and allegory interpenetrate: three as perfection (past-present-future; body-soul-spirit). The checkered pavement—so dear to Masonic iconography—suggests the board on which the collective destiny is decided. The diagonal light turns the Horatii into living columns; the capitals in the background bear the moral weight. In a contemporary key, the canvas reminds us that classicism can narrate collective emotions without renouncing the severity of the design.

Reception and legacy: the work was read in 1785 as a civic program before the Revolution; in 2026, its rhetoric returns in public campaigns that recover the solemnity of democratic rituals: to swear, to promise, to give one's word.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Oath of the Horatii (Jacques-Louis David) at KUADROS

3) The Death of Socrates, Jacques-Louis David (1787)

Socrates turns the sentence into liturgy. Sitting, with his index finger pointing to the sky, he delivers a final catechesis: the soul is immortal, virtue is non-negotiable. Twelve disciples are arranged around him like a grieving zodiac; the master occupies the place of the sun. The cup with hemlock, extended by a servant, is a secular Eucharistic cup. The bare columns are trees of knowledge; the folds of the cloaks, a raging sea that the philosopher's moral geometry calms.

The painting dramatizes a rite of passage: from time to eternity. The rectangle of the bed, the square of the seat, the cylinder of the cup, the triangle of the raised arm: a geometric catechesis. In the era of post-truth, the painting regains vigor as an emblem of coherence: accepting the consequences of thinking. Architects and designers of 2026 return to this “mother scene” to remind that form can be visible ethics.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Death of Socrates (Jacques-Louis David) at KUADROS

4) The Coronation of Napoleon, Jacques-Louis David (1805–1807)

.jpg?width=1200)

David erects an altar of modern power with ancient grammar. The basilical arch, the golden vault, and the procession of dignitaries configure a terrestrial Milky Way. Napoleon, self-invested, appears as a solar hero; Josephine, kneeling, is a receptive moon; the pope, mediator between worlds, acts as Mercury. The staging is astrological: each dignitary occupies a “degree” of that political sky. The reds and golds insist on Mars and Sun; the whites, on Jupiter (law) and Venus (harmony).

The painting has been read as propaganda, but its magnetism comes from an older alchemy: transforming will into rite. The gesture of crowning oneself inverts the Catholic sacrament; it declares a new civil priesthood. In 2026, this theater continues to challenge: how much of our public rituals is living symbol and how much empty decoration? The classicist return responds by proposing sober, understandable ceremonies where emblems regain meaning.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Coronation of Napoleon (Jacques-Louis David) at KUADROS

5) The Intervention of the Sabine Women, Jacques-Louis David (1799)

.jpg?width=1200)

In the center, Hersilia raises her arms in a cross stopping the slaughter between Romans and Sabines: a psychostasis — weighing of souls — in a civil key. The triangle formed by her arms and the diagonal of spears trace a hermetic seal of reconciliation. The Doric architecture in the background establishes a severity that subdues chaos. Seven primordial figures activate the planetary reading: Mars (warriors), Venus (Hersilia bridge), Saturn (the old), Mercury (bearer child), Jupiter (implicit law), Moon (veils), Sun (clear central illumination).

More than “abduction,” David paints an intervention: the feminine principle interrupts the cyclical revenge. In a 2026 marked by polarization, this scene offers a myth for mediation: classical beauty as a tool for peace. Its legacy is urbanistic: squares and parliaments that adopt geometries of encounter (semicircles, porticoes) instead of fronts of clash.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Intervention of the Sabine Women (Jacques-Louis David) at KUADROS

6) Liberty Leading the People, Eugène Delacroix (1830)

Although a romantic emblem, the work breathes classicism through its central allegory —Marianne, the civic goddess— and its compositional pyramid. The Phrygian cap resumes a Roman iconographic line; the tricolor flag acts as an alchemical talisman (red=Sulfur, white=Salt, blue=Mercury). Delacroix places the corpses in the foreground as a telluric base; above them rises the female figure as a stella maris guiding. The golden ratio underlies the placement of the flag and Marianne's head: the myth needs measure to be credible.

The recent restoration revived its original colors, reminding us that symbols also oxidize. In the civic landscape of 2026 —with digitized protests and ephemeral gestures— the painting reminds us that freedom is not a hashtag but a rite, a body that advances, a collective breath. The returning classicism takes note: readable allegories for common causes.

Buy an oil reproduction of Liberty Leading the People (Eugène Delacroix) at KUADROS

7) The Oath of the Tennis Court, Jacques-Louis David (1791, project)

Unfinished as a monumental painting, the project survived in drawings and versions that suffice to understand its power. The raised arms of the deputies are columns that replace those of an ancient temple: the people as architecture. A large window lets in light —a secular epiphany— that legitimizes the oath. The whole is a treatise on classicist iconography applied to politics: rhythmic repetition, open symmetries, axial axis.

The work prefigures the modern notion of political “performativism”: to say is to do. In 2026, its echo animates civil ceremonies —land possession ceremonies, community assemblies— that seek simple and solemn images. Classicism lends its grammar to shape commitment.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Oath of the Tennis Court (Jacques-Louis David) at KUADROS

8) The Abduction of Helen, Guido Reni (c. 1631)

Reni composes a machine of mythology: Helena —earthly Venus— is seized by Paris; around, soldiers and maidens orbit like planets. The overcast sky prophesies the war of Troy. In the key of alchemy, the forced union of beauty and disordered desire produces iron (Mars). Dogs and monkeys, sometimes present in related versions, remind us that unbridled eros animalizes.

The number of horses and lances usually refers to the four elements: fire (impulse), air (dust), water (tears), earth (weight of the chariot). At present, painting returns uncomfortable questions about agency and violence; the classicism that returns does not romanticize the myth, it examines it. Its visual legacy —curtains that inflate like sails, marble bodies— feeds photographers and filmmakers seeking an epic measure.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Abduction of Helena (Guido Reni) at KUADROS

9) The Banquet of Cleopatra, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1743–1744)

Cleopatra dissolves a pearl in vinegar and drinks it before Mark Antony: courtly alchemy. The pearl —mineral moon— is sacrificed in the acid (mercury water) to become solar liquor. Tiepolo stages this pagan mass with Corinthian architecture and skies that open like a curtain. Everything is classical theater in service of the myth of luxury and its transience.

Iconography and economy dialogue: banquets, tapestries, columns, slaves. The composition balances verticals (columns) and diagonals (glances, arms) in an invisible reticula that recalls Palladio. In 2026, the scene is re-read as an allegory of extreme consumption: turning natural heritage into spectacle. The classicism that returns is not blind to that irony; it uses solemnity to provoke awareness.

Buy an oil reproduction of The Banquet of Cleopatra (G. B. Tiepolo) at KUADROS

10) The Parnassus, Raphael (1509–1511)

Apollo and the Muses preside over the mountain of poetry. Raphael organizes a choir of poets —from Homer to Dante— in a semicircle: a zodiac of words. Apollo plays the lyre, the solar instrument par excellence; around, the music orders the spirit. The mountain is a vegetal dome; the clearing, a temple without walls. The frieze of bodies establishes the rhythm of inspiration: alternation of rest and ecstasy.

For 21st-century painters, El Parnaso offers a metapictorial manifesto: rather than style, classicism is an ethics of attention. Rhythm, proportion, and the hierarchy of accents are techniques to host the visit of the Muse. In 2026, when art is caught between saturation and silence, Rafael remembers that harmony is not anesthesia but finely tuned tension.

Buy an oil reproduction of El Parnaso (Rafael) at KUADROS

The return of classicism should not be understood as decorative nostalgia or a simple stylistic return, but as a conscious reactivation of principles that once again demonstrate their cultural, ethical, and social relevance. In this context, geometry recovers its liturgical character: triangles, circles, and rectangles cease to be ornaments to become instruments of concentration, mental order, and perceptual clarity. Form once again disciplines the gaze and, with it, thought.

This new classicism also reactivates allegory, but it does so in a dynamic and plural way. Ancient gods and symbolic personifications return not as relics but as contemporary incarnations of shared civic virtues. Figures like Marianne, Athena, or Venus-Prudence reappear to express collective values, open to interpretation and debate, far from unequivocal or dogmatic readings.

Light, in this framework, acquires an almost sacramental dimension. It is not used to manipulate emotion but to govern it rigorously: directed brightness and dramatic contrasts structure the visual experience, guide attention, and allow emotional intensity to arise from the composition itself, not from rhetorical excess.

This logic is complemented by a secular numerology that reaffirms the learning of order through counting. Triads, dodecads, and quaternities appear as reminders that understanding the world goes through repeatable, measurable, and shared structures. Counting, measuring, and proportioning become cultural acts rather than technical gestures.

Materiality also occupies a central place. The relearned classicism bets on stable pigments, durable supports, and conscious restorations, understood as intergenerational responsibility. The work is no longer conceived as an ephemeral object but as a deposit of time, care, and continuity.

This return does not ignore history nor idealize the past. On the contrary, it relies on a critical memory that expands the canon and dialogues with myths without hiding their problematic areas. Classicism is reinterpreted from contemporary awareness, accepting necessary tensions, contradictions, and revisions.

On the social plane, compositions regain their capacity to shape public conversation. Readable pyramids, friezes of equality, and clear structures visually organize the common space, proposing rhythms that favor collective understanding and civic exchange.

Technology, far from opposing this approach, serves the myth. High-resolution digitizations, faithful colorimetries, and open-access policies expand the reach of works and democratize their study, reinforcing their cultural and educational function.

From there arises a renewed pedagogy of measurement. Museums and schools reintroduce symbolic reading as a form of civic literacy, teaching how to interpret proportions, gestures, and structures as shared languages that organize social experience.

Ultimately, this relearned classicism proposes a cosmology of care. More than a style, it presents itself as an ethics based on limits, proportions, and pacts: a way of thinking about the world from responsibility, harmony, and the awareness that every form implies a relationship with others and with time.

Thus, the ten paintings explored here reveal that classicism does not return as a mask, but as a method: a way of seeing that turns the world into a readable text. In turbulent times, serenity is not escape: it is resistance with beauty.

KUADROS ©, a famous painting on your wall.

Hand-made oil painting reproductions, with the quality of professional artists and the distinctive seal of KUADROS ©.

Art reproduction service with a satisfaction guarantee. If you are not completely satisfied with the replica of your painting, we refund 100% of your money.