By reproducing paintings, KUADROS makes the dreams of many art buyers a reality.

The reproduction of paintings is a legitimate and long-standing business. However, there is a darker side to the art world when the authors of these reproductions try to deceive buyers by passing fake works as authentic.

Each year, numerous forgeries are displayed in museums, private collections, and art galleries.

The role of technology in art forgeries

The market is flooded with copies or replicas without anyone realizing that the real version is hanging in a museum or, unknowingly, that it is in a private collection. Regarding authorship attribution, some paintings go through several rounds of attribution because no one can discover who created them. The work may eventually be attributed to the school of a particular artist.

Art forgers have the tools to create versions of "authentic" art using science and skill to copy the style of an artist that not only includes the artwork itself but even provenance documents. When researching a painting, it is possible to find a similar one that is published more widely or that is found in the artist's catalog. The forged provenance documents that accompany the work may include letters or handwritten photographs. Some of the largest art forgers in history have even staged photographs with modern people dressed in period clothing alongside works of art to provide convincing documentation of a work's history.

The incentive to be a successful forger has skyrocketed; a single imitation of a master artist executed by experts can finance a long and comfortable retirement. The technologies available to assist aspiring forgers have also improved. Naturally, fraud has improved, triggering a crisis of authenticity for art world institutions, museums, galleries, and auction houses.

Forgers are becoming increasingly rigorous in collecting materials, taking the trouble, for example, to obtain wooden panels from furniture that they know can be attributed to the year of the forgery. (The trick is not completely new; Terenzio da Urbino, a 17th-century conman, sought dirty and old canvases and frames, cleaned them, and turned them into "Raphaels").

Venus, by Lucas Cranach the Elder

The unraveling of the plot of a series of forgeries of ancient masterpieces began in the winter of 2015 when French police appeared at a gallery in Aix-en-Provence and took a painting from the exhibition, Venus, created by the German Renaissance master Lucas Cranach the Elder. A exquisite forgery was discovered that had it all: oil on oak, 38 cm by 25 cm, dated 1531. The work was purchased in 2013 by the Prince of Liechtenstein for around £6 million. Venus was the undeniable star of the exhibition of works from his collection; she shone on the cover of the catalog. But an anonymous tip to the police suggested that she was, in fact, a modern forgery, so they picked her up and took her away.

Buy a reproduction of Venus - Lucas Cranach the Elder in the KUADROS online store

Another interesting example was the painting by Frans Hals, Portrait of a Gentleman, supplied to Sotheby's by Mark Weiss. The work was sold for about £8.5 million ($10.8 million), but it was later declared fake.

Portrait of a Gentleman (original), Frans Hals

Buy a reproduction of Portrait of a Gentleman (original) - Frans Hals in the KUADROS online store

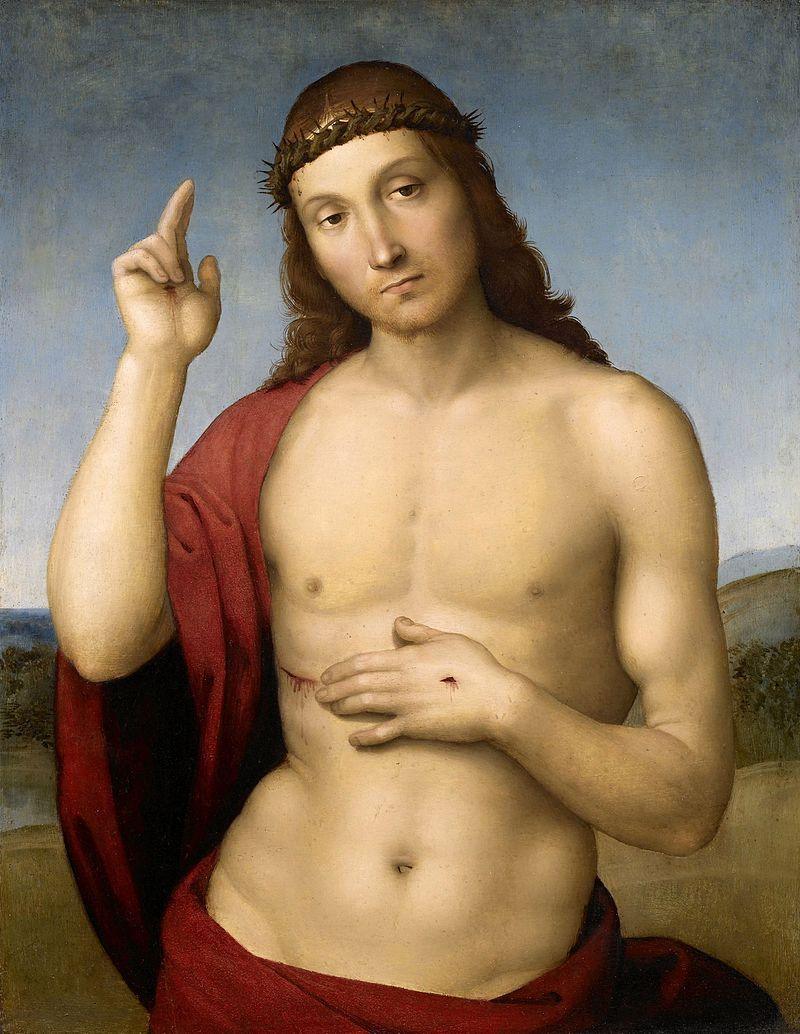

Salvator Mundi - Leonardo Da Vinci

The most expensive painting in the world, Da Vinci's portrait of Jesus that sold for £350 million to a Saudi prince, "may actually be a FAKE."

Salvator Mundi, a striking image of Jesus dubbed the male Mona Lisa, sold for a record $450 million (£342 million) in 2017 to a Saudi prince.

It was believed to be a long-lost but entirely authentic Da Vinci verified by experts from around the world.

But it turns out that the portrait was probably only "attributed, authorized, or supervised by" the Renaissance master.

In reality, it is now believed to have been painted by one of his assistants or students, with only a few brushstrokes, if any, from Da Vinci himself.

The degradation, first revealed by The Art Newspaper, will likely drastically reduce the legendary value of the painting.

The official buyer in 2017 was Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud, a little-known member of the Saudi royal family without a background as an art collector.

But it is widely accepted that he was buying the masterpiece on behalf of Prince Mohammed bin Salman, making him the true owner of the painting.

Art forgeries: a growing problem

Georgina Adam, who wrote the book Dark Side of the Boom detailing the excesses of the art market, said that many forgers are wisely choosing to forge 20th-century painters who used paints and canvases that can still be obtained and whose abstractions are easier to imitate. "The technical skill needed to forge a Leonardo is colossal, but with someone like Modigliani, it is not," she argued. "Scholars will say they are easy to distinguish, but the fact is that it is not easy at all." At a celebrated Modigliani exhibition in Genoa, it was revealed that 20 of the 21 paintings displayed were forgeries. As the wave of money in the market has increased, making decisions about the authenticity of these works has become an imperative necessity.

The works of ancient and modern masters, whose art is sold at auction, are usually the most forged art. If collectors or museums seek to acquire this type of art, some tasks that can be completed before the acquisition include scientific analysis, historical research, and obtaining a certificate of authenticity. Reports can be placed in the database of the Illustration Archive to ensure that the data remains securely with the illustration archive.

Some years ago, handshake deals in art transactions were the norm when two massive forgery scandals sent chills through the art world. Everyone who relied on the market had been deceived. Christie's and Sotheby's sold the forgeries, experts authenticated them, the MET in New York and other museums exhibited them, major distributors distributed them. In 2010, Wolfgang Beltracchi was arrested in Germany and admitted to forging 20th-century masters like Max Ernst and Fernand Léger. The forgeries numbered in the hundreds.

A year later, the prestigious gallery Knoedler & Company, one of the oldest in New York, closed amid accusations that it had sold about $60 million worth of fake abstract expressionist paintings. The accusations later turned out to be correct. The federal judge in Manhattan, Paul Gardephe, ruled that Knoedler and its former director Ann Freedman had to go to trial in two lawsuits filed by angry buyers, New York collector John Howard and Sotheby's chairman Domenico de Sole and his wife, Eleanore. Knoedler and Freedman deny any wrongdoing and say they were also deceived. Freedman's attorney, Luke Nikas, told The Art Newspaper that in the trial she "will tell her story and demonstrate her good faith."

50% of the world's artwork may be forgeries

In 2014, a report from the Swiss Institute of Fine Art Experts (FAEI) stated that at least half of the artworks circulating in the market today are fake. Others argue that the percentage is lower. Nevertheless, considering the size of the art market, which was estimated at $45 billion in 2014, money has been spent recklessly among collectors and museums. Unless all dealers, museums, auction houses, and collectors are willing to pay for scientific analysis, research, and obtaining an expert opinion, there is no way to rid the market of forgeries. Many art experts are increasingly reluctant to authenticate works due to the possibilities of being sued for incorrect attribution or refusing to authenticate the work.

“The reaction at this moment is pure terror: nothing hits the art world like the ability of an asset to turn to smoke 100%. The systems and structures that are supposed to be reliable are not," says Jeffrey Taylor, who teaches arts management at the State University of New York at Purchase.

How to deal with this new uncertainty?

Given the ease with which forgeries enter the market, it seems obvious that art world experts should no longer be satisfied with a traditional line item invoice and the gallery's oral guarantees of authenticity.

Several years after Beltracchi's arrest, it's time to ask what market players have learned. Are they verifying provenance more carefully, consulting experts, and obtaining written guarantees from galleries?

What has changed?

"Nothing," says art consultant Todd Levin, echoing other figures in the art world. Others see what art lawyer Peter Stern calls "evolution." "More sophisticated buyers are more cautious," he says. “Advisors do everything they can to verify authenticity for them.

However, there is a consensus that the same obstacles to determining authenticity highlighted by Knoedler and Beltracchi remain formidable because the ways of doing business have changed little, if at all. Consider provenance. If a work can be traced from the current owner back to the artist, it is almost a guarantee of authenticity. But the art market is known for its lack of transparency. With galleries as intermediaries, even the seller's name is often not revealed to the buyer. Knoedler collectors paid millions even though the fictitious owner was never named. The gallery itself knew him only as Mr. X. (Mr. X was invented by Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales, who brought the forgeries to Knoedler; in 2013 she pleaded guilty to tax evasion, fraud, and money laundering).

Anonymity in art selling

The anonymity of the seller is likely to remain one of the rules of the game. "I don't see things changing regarding participants' willingness to identify themselves, so due diligence can be difficult," says Judd Grossman, who represented the first collector to sue Knoedler and Freedman. (Ten lawsuits were filed. Four, including Grossman's, were settled on undisclosed terms). "Sellers have the right to remain anonymous," says Achim Moeller of Moeller Fine Art. Even if there is documentary evidence of provenance, it can also be convincingly forged. Beltracchi told buyers that the forgeries were picked up by his wife's grandparents. He took photographs of her posed in front of a series of forgeries and dressed them in period styles. "It was brilliant," comments art consultant Liz Klein.

Buyers may consult an authenticator, but "they are increasingly cautious" for fear of being sued, says attorney Stern. Experts involved in the Beltracchi and Knoedler scandals have been taken to court both in the United States and Europe. And many artist foundations have shut their authentication boards in light of the legal fees incurred by the Andy Warhol Foundation to vindicate itself in an authentication lawsuit. In 2007, a collector named Joe Simon-Whelan sued the Andy Warhol Foundation's authentication committee, alleging that it had twice rejected a Warhol serigraph he owned because it wanted to maintain scarcity in the Warhol market. Four years later, after spending $7 million on legal fees, the committee was dissolved.

The collapse of these committees feels like a victory for market forgers over academia, a blow to the real cause of reliable authentication. At least in New York, a small group of lawyers is pushing for legislation to protect academics from being sued merely for expressing their opinion.

Where does this leave buyers?

They never know what experts might think, says Dean Nicyper, an art lawyer who, along with the New York City Bar Association, is advocating for legislation that would make it difficult to sue authenticators. Buyers can get some guarantees with the customary type of written agreements in other commercial transactions. A gallery may reveal the seller's name if the buyer's lawyer signs a confidentiality agreement, for example. "Most galleries will solve a problem if asked," says art consultant Klein. But that is not how the art market typically works. Unlike buying a house, where everyone has a lawyer, Grossman points out, art is "one-of-a-kind and buyers don't want to lose the deal by involving a lawyer."

Klein says that some collectors buy from someone they trust and leave it at that because they are seduced by social things, know artists, and think their lives become more interesting.

One person who has changed his way of operating is veteran dealer Richard Feigen, who was an intermediary in the sale of a Knoedler forgery. "I relied too much on Knoedler's reputation [...], so I did not examine it with the care I would have with an individual or a gallery with less reputation," he says. "That was a mistake, and I learned from it."

Collectors in the Knoedler lawsuits said they too trusted Knoedler's reputation. In their court documents, Knoedler and Freedman argued that since the buyers were sophisticated, that trust was unreasonable. Judge Gardephe said that was a question the jury would have to decide. Working with a reputable gallery is still very useful.

If you buy from a reputable dealer, your due diligence is partly owed to that dealer, says the president of the Dedalus Foundation, Jack Flam. Flam was instrumental in exposing the forgeries at Knoedler when Dedalus discovered that the gallery was selling fake Robert Motherwells. Observers think that trust is warranted: "The best galleries have always done and will continue to do their homework," says art lawyer Grossman. Forensic analysis confirmed the forgeries at Knoedler and Beltracchi, and may be the best protection for art sold in the secondary market.

Technology to the rescue

The forensic business is growing, says Nicholas Eastaugh, director of Art Analysis & Research based in London, who identified the first Beltracchi forgery. Technology will play an important role in the art world.

In January 2018, the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent exhibited 26 fake works, which were loaned by a collector. The paintings, by 20th-century Russian artists Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky, were deemed fake by academics who noticed that the works were not included in any of the artists' catalogs. The Art Newspaper stated that "they have no exhibition history, have never been reproduced in serious academic publications, and have no traceable sales records." Furthermore, the museum did not conduct scientific analyses on the works because it is only standard policy for acquisitions, not loans.

The Telegraph also reported that a collection of 21 paintings by Amedeo Modigliani, which were on display at the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, were announced as fake. Modigliani is one of the most copied artists in the world, and his paintings sell for millions. French expert on Modigliani, Marc Restellini, believes there are over 1,000 fake Modigliani paintings in the world. The exhibition closed in July and the paintings were turned over to the police for investigation.

Then, a small museum in southern France realized that 60% of its collection was fake. The Etienne Terrus Museum hired an art historian to reorganize the museum, who discovered that 80 paintings that the museum recently acquired were not by the artist Etienne Terrus. He noted discrepancies between the materials used to construct the canvases in the forgeries versus what Terrus used. He also mentioned to The Guardian that "in one painting, the ink signature was erased when I ran my white glove over it."

Later, two experts stated that a painting supposedly by Parmigianino, auctioned through Sotheby's in 2012, was fake. Sotheby's rescinded the sale in 2015 after hiring a scientific analyst to confirm the presence of a modern synthetic green pigment called phthalocyanine in more than 20 locations in the artwork. Sotheby's turned around and sued the seller. The painting had been exhibited in Parma, Vienna, and New York after the Sotheby's auction according to The Art Newspaper.

What the future holds

It is possible to imagine the perfect forgery, one that defeats scientists and art connoisseurs. Our villain is a talented copyist, well practiced in the style and themes of their chosen artist. They are also an ingenious procurer of materials, capable of creating all kinds of canvases, frames, pigments, and binders appropriate to their age. Their forgery fits perfectly into a chain of provenance, giving it the title of a now-lost work or providing false documents to claim that it had been part of a well-known private collection.

Theoretically, if each of these steps is executed perfectly, there should be no way to expose the painting as fake. It will be a work of art in every sense but one. But today's world, the world in which the forgery is being created, is likely to fix something firmly within the painting, for example, radioactive dust, perhaps, or a cat hair, or a lost polypropylene fiber. When that happens, only the scientist can hope to catch it.

Science has a way of showing the sagacity of academics. In a 1932 trial in Berlin, the first in which forensic examination was used to examine art, two connoisseurs debated the authenticity of a set of 33 canvases, all supposedly by Vincent van Gogh. All the paintings were sold by an art dealer named Otto Wacker. It took a chemist, Martin de Wild, to trace resins in the paint that Van Gogh had never used, and to demonstrate that the paintings were fake.

Since then, science has improved, even as human judgment has remained unchanged, vulnerable to the excitement of discovering lost masterpieces and the pressures of the market.

KUADROS ©, a famous painting on your wall.