Throughout the centuries, Christian art has featured many different types of painting, executed in a wide range of media.

Religious art uses religious themes and motifs that generally have a recognizable moral narrative or attempt to induce strong spiritual emotions in the viewer. In the Western world, religious art can be defined as any work of art that has a Christian theme. Western religious painting is dominated by scenes from the Old Testament and from the life of Jesus Christ.

Among the most represented themes are the representations of the Virgin Mary with the child Jesus and Christ on the cross. Many of the most famous religious paintings were created during the Renaissance, an influential cultural movement that originated in Italy.

The three great Renaissance masters Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael appear several times on this list. Kuadros brings you the 10 most famous religious paintings.

No.1 The Creation Of Adam - Michelangelo (1512)

The most famous section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling is Michelangelo's Creation of Adam. This scene is located next to the Creation of Eve, which is the panel in the center of the room, and the Congregation of the Waters, which is closer to the altar.

The work done by Michelangelo is a cornerstone of Renaissance art. The painting illustrates the biblical narrative of creation from the book of Genesis in which God breathes life into Adam, the first man.

The Creation of Adam differs from the typical Creation scenes painted up to that time. Here, two figures dominate the scene: God on the right and Adam on the left. God is shown within a floating nebulous form made up of curtains and other figures. The form is supported by angels who fly without wings, but whose flight is clearly seen by the sprouting curtains below them. God is depicted as an elderly but muscular man with gray hair and a long beard who reacts to the forward motion of flight. This is a far cry from the imperial images of God that had otherwise been created in the West and date back to the time of late antiquity. Instead of wearing royal clothes and depicted as an all-powerful ruler, he only wears a light robe that leaves much of his arms and legs exposed. It could be said that it is a much more intimate portrait of God because he is shown in a state that is not untouchable and remote from Man, but accessible to him.

Unlike the figure of God, who is stretched out and aloft, Adam is depicted as a lazy figure who responds nonchalantly to God's imminent touch. This touch will not only give life to Adam, but it will give life to all mankind. It is, therefore, the birth of the human race. Adam's body takes on a concave shape that echoes the shape of God's body, which is in a convex posture within the nebulous, floating form. This correspondence of one form with another seems to underline the larger idea that Man corresponds to God; that is, it seems to reflect the idea that Man has been created in the image and likeness of God, an idea with which Michelangelo must have been familiar.

The painting has been extensively analyzed and, among other things, the edges of the painting have been found to correlate with grooves on the inner and outer surface of the cerebrum, brain stem, basilar artery, pituitary gland, and optic chiasm. . The hand of God does not touch Adam, but Adam is already alive as if the spark of life is transmitted through a synaptic cleft. Beneath the right arm of God is a sad angel in an area of the brain that is sometimes activated on PET scans when someone experiences a sad thought. God overlaps the limbic system, the emotional center of the brain and possibly the anatomical counterpart of the human soul. The right arm of God extends to the prefrontal cortex, the most creative and uniquely human region of the brain; the red cloth that surrounds God is in the shape of a human womb; and the green scarf is believed to be a freshly severed umbilical cord. The Creation of Adam is perhaps the best known painting after Mona Lisa; and along with The Last Supper, it is the most replicated religious painting of all time. The image of the almost touching hands of God and Adam has become an icon of humanity and has been imitated and parodied countless times.

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel suffered from the damaging effects of centuries of smoke which had caused the ceiling to darken considerably. It was not until 1977 that the cleaning of the roof began. The cleanup was amazing after its completion in 1989; what was once dark and monotonous has become vivid. The change from pre-cleaning to post-cleaning was so great that some initially refused to believe that this was how Michelangelo painted. Today, we have a much better understanding of Michelangelo's color palette and the world he painted, beautifully captured on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Buy a reproduction of The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo at Kuadros online store

No.2 The Last Supper - Leonardo Da Vinci (1495-1498)

Last Supper, or the Italian Cenacolo, one of the most famous works of art in the world, painted by Leonardo da Vinci probably between 1495 and 1498 for the Dominican monastery Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

This famous painting depicts the dramatic scene described in several closely related moments in the Gospels, including Matthew 26:21-28, in which Jesus declares that one of the Apostles will betray him and then institute the Eucharist. According to Leonardo's belief that posture, gesture and expression should manifest the "notions of the mind", each of the 12 disciples reacts in such a way that Leonardo considered suitable for the personality of the apostles. The result is a complex study of various human emotions, expressed in a deceptively simple composition.

Leonardo had not worked on such a large painting and was inexperienced in the standard mural medium of fresco. The painting was done using experimental pigments directly on the dry plaster wall and, unlike the frescoes, where the pigments are mixed with the wet plaster, it has not stood the test of time well. Even before it was finished, there were problems with peeling paint on the wall and Leonardo had to repair it. Over the years it has collapsed, been vandalized, bombed and restored. Today we are probably seeing very little of the original painting.

The theme of the Last Supper is Christ's final meal with his apostles before Judas identifies Christ to the arresting authorities. The Last Supper (it is believed to correspond to the Jewish Passover Seder), is remembered for two events: Christ tells his apostles “One of you will betray me”, and the apostles react, each according to their personality. Referring to the Gospels, Leonardo depicts Philip asking "Lord, is it I?" Christ answers: “Whoever puts his hand in the dish with me will betray me” (Matthew 26). We see Christ and Judas simultaneously reaching for a plate between them, even as Judas backs away defensively. Leonardo also simultaneously represents Christ blessing the bread and saying to the apostles “Take, eat; this is my body” and blessing the wine and saying “Drink from it all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is shed for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26). These words are the founding moment of the sacrament of the Eucharist (the miraculous transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ).

The balanced composition is anchored by an equilateral triangle formed by the body of Christ. It sits below an arched pediment which, if completed, traces a circle. These ideal geometric forms refer to the Renaissance interest in Neoplatonism (an element of the humanistic Renaissance that reconciles aspects of Greek philosophy with Christian theology). In his allegory, "The Cave," the Greek philosopher Plato emphasized the imperfection of the earthly realm. Geometry, used by the Greeks to express heavenly perfection, has been used by Leonardo to celebrate Christ as the embodiment of heaven on earth. Leonardo drew a green landscape beyond the windows. Often interpreted as a paradise, it has been suggested that this heavenly sanctuary can only be reached through Christ. The twelve apostles are arranged in four groups of three and there are also three windows. The number three is often a reference to the Holy Trinity in Catholic art. In contrast, the number four is important in the classical tradition (for example, Plato's four virtues).

Ever since the Last Supper was completed, when it was declared a masterpiece, the mural has garnered praise from artists like Rembrandt van Rijn and Peter Paul Rubens and writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. It has also inspired countless reproductions, interpretations, conspiracy theories, and works of fiction. The delicate state of the Last Supper has not diminished the painting's appeal; instead, it has become part of the legacy of the artwork.

Buy a reproduction of The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci at Kuadros online store

No.3 The Return of the Prodigal Son - Rembrandt (1669)

In the parable of the prodigal son, a father has two sons; the youngest asks for his inheritance, wastes his fortune and returns home after being left destitute. He intends to beg his father to make him one of his servants, but the father instead celebrates his return. When his eldest son objects, the father tells him that they are celebrating because his brother, who was lost, has now come to his senses.

Rembrandt's last word is given in his monumental painting of the Return of the Prodigal Son. Here he interprets the Christian idea of mercy with extraordinary solemnity, as if this were his spiritual testament to the world. It goes beyond the works of all other Baroque artists in evoking religious humor and human sympathy. The aged artist's power of realism does not diminish, but rather increases with psychological insight and spiritual awareness. The lighting and the expressive color and the magical suggestion of his technique, together with a selective simplicity of setting, help us to feel the full impact of the event.

The main group of the prodigal father and son stands out in light against a huge dark surface. Particularly vivid are the son's tattered dress and the old man's sleeves, which are stained ocher with golden olive; the ocher color combined with an intense scarlet red on the father's mantle forms an unforgettable color harmony. The observer awakens to the sensation of some extraordinary event. The son, ruined and disgusting, with a bald head and the appearance of an outcast, returns to his father's house after long wanderings and many vicissitudes. He has squandered his inheritance on foreign lands and has sunk into vagrant status.

His elderly father, dressed in rich robes, like the attending figures, has hastened to meet him at the door and greets the long-lost son with the greatest fatherly love. The event is devoid of any momentary violent emotion, but rises to a solemn calm that lends the figures some of the qualities of statues and gives the emotions a lasting character, no longer subject to the changes of time. Unforgettable is the image of the repentant sinner leaning on his father's chest and the elderly father bending over his son. The father's features speak of a sublime and august goodness; so do his outstretched hands, not free from the stiffness of old age. The set represents a symbol of every return home, of the darkness of human existence illuminated by tenderness, of weary and sinful humanity that takes refuge in the refuge of God's mercy.

The inherent message conveyed by this famous painting is clear. God will always forgive a repentant sinner, no matter what.

The religious iconoclasm that occurred after the liberation of Holland from the colonial yoke of Spain and the Catholic Church turned Calvinist churches into bare shells, dedicated to worship, preaching, and prayer. The Dutch authorities had no desire to decorate their places of worship with altarpieces, frescoes, or any other kind of religious art to speak of.

Instead, Holland became famous for Dutch Realism, a type of small-scale, detailed, and highly realistic style of genre painting and portraiture, many of which contained moralistic messages of various kinds.

A third type of art that Dutch realist artists excelled at was still life painting (especially Vanitas painting), which also contained a moral, sometimes religious, message. This was the closest many Dutch came to "Protestant art".

It is therefore all the more surprising that a Dutch Protestant painter like Rembrandt should become such an insightful interpreter of Biblical scenes.

Buy a reproduction of The Return of the Prodigal Son - Rembrandt in the Kuadros online shop

No.4 The Wedding Feast At Cana - Paolo Veronese (1562-1563)

The subject of this famous painting is based on the biblical story told in the Gospel of Saint John (John 2: 1-11), about a marriage celebrated in Cana, Galilee, attended by Mary, Jesus and their disciples. Toward the end of the wedding feast, when the wine begins to run out, Jesus calls for stone jars to be filled with water, which the master then turns into wine. This episode, the first of the seven signs of the Gospel of John that testify to the divine condition of Jesus, is a precursor to the Eucharist.

The Marriage at Cana (or The Wedding Feast at Cana) by Paolo Veronese is an oil on canvas painting that was painted in 1563 for the Benedictine Monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. Veronese transposed the biblical story into the more modern setting of a typically extravagant Venetian wedding.

The Wedding at Cana combines elements from several different styles, adapting High Renaissance disegno to the composition - exemplified by the works of Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo. To this he added one or two features of Mannerism, as well as a number of allegorical and symbolic features.

The content of the painting also consists of a complex mix of the sacred and the profane, religious and secular, theatrical and mundane, European and Eastern. Rendered in the grand style of contemporary Venetian society, the banquet takes place within a courtyard flanked by Doric and Corinthian columns and bordered by a low balustrade. In the distance you can see a porticoed tower, designed by the Padua-born architect Andrea Palladio. In the foreground, a group of musicians plays various lutes and stringed instruments. Musical figures include the four great painters of Venice: Veronese himself (dressed in white, playing viola da gamba), Jacopo Bassano (on flute), Tintoretto (violin), and Titian (dressed in red, playing cello).

Diners at the wedding table, all waiting to be served wine for the dessert of the meal, include: the bride and groom (seated at the far left of the table), Jesus Christ (center of the table), surrounded by Mary and the Apostles , along with a bewildering array of royalty, nobles, officials, clerks, servants and others, representing a cross-section of Venetian society and variously dressed in Biblical, Venetian or Oriental costumes and adorned with sumptuous hairstyles and wares jeweler's. Numerous historical figures appear in The Marriage at Cana, including: Emperor Charles V, Eleanor of Austria, Francis I of France, Mary I of England, Suleiman the Magnificent, Vittoria Colonna, Giulia Gonzaga, Cardinal Pole, and Sokollu Mehmet Pasa. In total, some 130 unique figures are depicted in this famous religious painting.

In the work, the religious symbols of the Passion are included together with luxurious vessels and silverware from the 16th century. The furniture, the chest of drawers, the jug and the crystal glasses and vases reveal the party in all its splendor. Each guest at the table has an individual place, complete with napkin, fork and knife. In this duplication of meaning, no detail escapes the artist's eye.

The painter selected expensive pigments imported from the East by Venetian merchants: orange yellows, deep reds and lapis lazuli are widely used in curtains and in the sky. These colors play an important role in the legibility of the painting; they contribute, through their contrasts, to the individualization of each one of the figures.

NOTE: While many figures in the image are interacting with each other, none of them are actually talking. This is to comply with the code of silence observed by all Benedictine monks in the refectory where the painting was to be hung.

The Wedding Feast at Cana contains a great deal of symbolism. The entire work, for example, symbolizes the interplay between earthly pleasure and earthly mortality. Behind the balustrade, on the figure of Jesus, an animal is sacrificed, alluding to the next sacrifice of Jesus, such as the Lamb of God, a reference that is supported by the dog chewing a bone at the bottom of the painting. Meanwhile, to the left of Jesus, the Virgin Mary cups her hands to represent a glass that will contain the new wine of humanity, that is, the Blood of Christ. Also, in front of the musicians is an hourglass, a standard reference to the fleetingness of earthly pleasures, including human vanity.

The Benedictines of the San Giorgio Maggiore monastery in Venice commissioned this immense painting in 1562 to decorate their new refectory. The contract that committed Veronese to the realization of the wedding banquet was extremely precise. The monks insisted that the work be monumental, in order to fill the entire back wall of the refectory. Hanging at a height of 2.5 meters from the ground, it was designed to create an illusion of extended space. This 70 m² work occupied Veronese for 15 months, most likely with the help of his brother Benedetto Caliari. The commission was a turning point in Veronese's career; after the success of the painting, other religious communities would clamor for similar work in their own monasteries. Despite its exceptional dimensions, the painting was confiscated, rolled up, and shipped to Paris by Napoleon's troops in 1797.

Buy a reproduction of The Marriage At Cana by Paolo Veronese in the Kuadros online store

No.5 The School Of Athens - Raphael (1509-1511)

Millions of eyes have marveled at the eternal gathering of ancient philosophers and mathematicians, statesmen and astronomers that Rafel luminously imagines in his famous fresco.

In particular, Raphael's fresco The School of Athens has come to symbolize the union of art, philosophy, and science that was a hallmark of the Italian Renaissance. Painted between 1509 and 1511, it is located in the first of the four rooms designed by Raphael, the Stanza della Segnatura. At that time, a commission from the Pope was the pinnacle of any artist's career. For Rafel, it was validation of an already flourishing career.

Raphael rose to the challenge, creating an extensive catalog of preparatory sketches for all of his frescoes. These would later be expanded into full-scale cartoons to help transfer the design to wet plaster. Working at the same time as Michelangelo on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, this is believed to have helped drive and inspire Raphael by stimulating his competitive nature.

Rafel took the idea to a whole new level with massive compositions reflecting philosophy, theology, literature, and jurisprudence. Read as a whole, they immediately conveyed the pope's intellect and would have sparked a discussion among educated minds lucky enough to enter this private space. The School of Athens was the third painting completed by Raphael after Disputa (representing theology) and Parnassus (representing literature). It is placed in front of Disputa and symbolizes philosophy, establishing a contrast between religious and secular beliefs.

Set in an immense architectural illusion, The School of Athens is a masterpiece that visually represents an intellectual concept. In one painting, Raphael used groupings of figures to present a complex lesson on the history of philosophy and the different beliefs that the great Greek philosophers developed. Raphael would certainly have been aware of the private exhibitions of the Sistine Chapel in progress that were organized by Bramante.

Who are the figures of The School of Athens?

The two thinkers in the very center, Aristotle, on the right, and Plato, on the left, pointing upwards, have been enormously important to Western thought in general. In different ways their different philosophies were incorporated into Christianity.

To the left of Plato, Socrates is recognizable thanks to his distinctive features. Raphael is said to have been able to use an ancient portrait bust of the philosopher as a guide. He is also identified by the gesture of his hand, as Giorgio Vasari points out in The Lives of the Artists.

In the foreground, Pythagoras sits with a book and an inkwell, also surrounded by students. Although Pythagoras is well known for his mathematical and scientific discoveries, he was also a strong believer in metempsychosis.

Mirroring Pythagoras's position on the other side, Euclid is bent over to demonstrate something with a compass. His young students eagerly try to grasp the lessons he is teaching them.

The great mathematician and astronomer Ptolemy is right next to Euclid, with his back to the viewer. Wearing a yellow robe, he holds a terrestrial globe in his hand. The bearded man standing before him holding a celestial globe is believed to be the astronomer Zoroaster. Interestingly, the young man standing next to Zoroaster, looking at the viewer, is none other than Raphael himself. Incorporating this type of self-portrait is not unheard of at the time, although it was a bold move for the artist to incorporate his likeness into a work of such intellectual complexity.

It is universally accepted that the old man lying on the steps is Diogenes. Founder of Cynic philosophy, he was a controversial figure in his time, living a simple life and criticizing cultural conventions.

One of the most striking figures in the composition is a pensive man seated in the foreground, his hand on his head in a classic “thinker” position.

In the realm of philosophers, he is Heraclitus, a pioneer of self-taught wisdom. He was a melancholy character and did not enjoy the company of others, making him one of the few isolated characters in the fresco.

Completing Raphael's program, two large statues sit in niches at the rear of the school. To Plato's right, we see Apollo, while to Aristotle's left is Minerva. Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and justice, is a fitting representative of the moral philosophy side of the fresco. Interestingly, her positioning also brings her closer to Raphael's fresco on jurisprudence, which unfolds directly to her left.

Buy a reproduction of The School of Athens by Raphael in the Kuadros online store

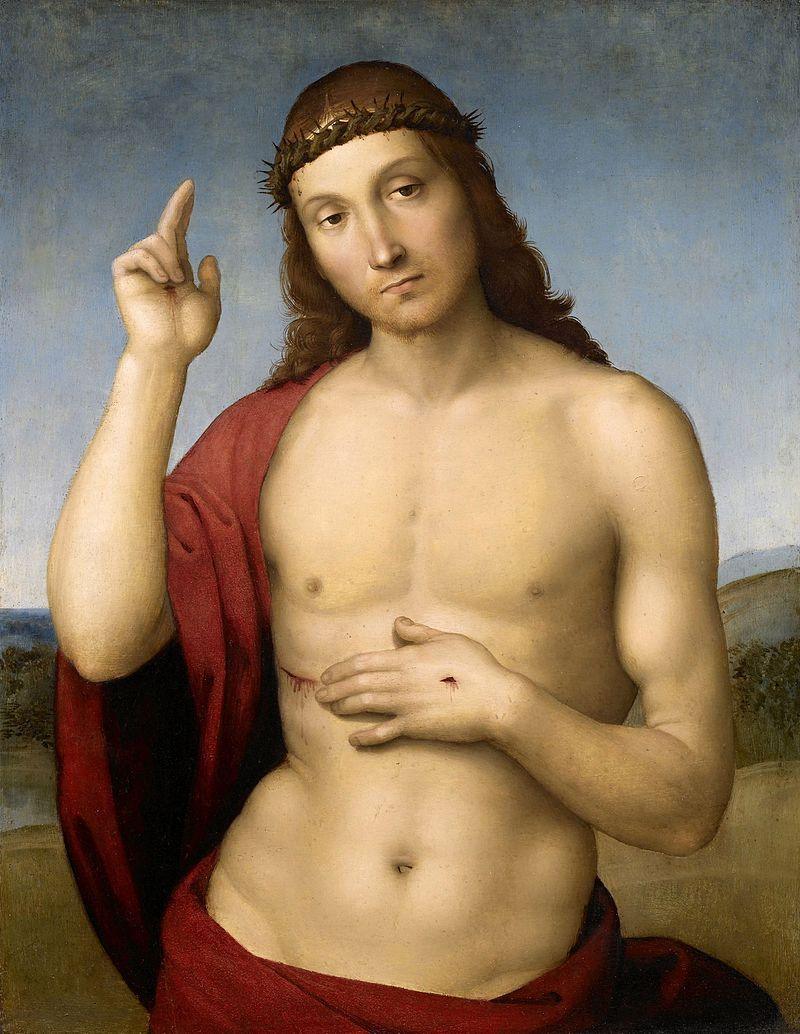

No.6 The Transfiguration - Raphael (1520)

Commissioned in 1517 by Cardinal Giulio de' Medici (1478-1534) (of the Florentine Medici family), soon to become Pope Clement VII (1523-34), as an altarpiece for the French Narbonne Cathedral (in competition with The Raising of Lazarus by Sebastiano del Piombo) of whom he was archbishop, this famous work of religious art was left unfinished by Raphael on his death in 1520, and was completed by his assistants Giulio Romano (1499-1546) and Giovanni Francesco Penni (1496- 1536).

After all, the cardinal kept the painting in Rome and, upon accession to the papacy in 1523, gave it as a gift to the church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome. In 1774, the new Pope Pius VI (1775-99) had a mosaic copy made and installed in St. Peter's Basilica. The painting itself was looted by Napoleon in 1797 and taken to Paris, from where it was repatriated in 1815.

This work narrates two unrelated biblical events. Above is the story of the transfiguration of Christ. At the bottom is the story of a young man who is possessed by a demon.

Jesus is shown on top of Mount Tabor (Israel) in a shimmering snow-white robe and beside him the prophets Moses on the right and Elijah on the left. The clouds behind Jesus are illuminated. Jesus raises his arms and looks towards God.

Below Jesus are three of his disciples, from left to right, James, Peter, and John. They cover their faces with their hands because the sky is too bright for their eyes. The two figures on the left are probably Justus and Pastor. These are two Christian martyrs to whom the church in which the painting was initially intended to be placed is dedicated.

Below you can see the nine disciples of Jesus who did not go up the mountain positioned on the left side. They try to heal a young man who is possessed by an evil spirit. The blue-robed figure at lower left is probably Mateo. He consults a book but cannot find the solution to cure the young man. The young disciple in the yellow robe is Felipe. To the right of Felipe, with the red tunic, is Andrés. The man behind Andrés, pointing to the sick child, is Judas Tadeo, and the older man to his left is Simon. The man on the far left is probably Judas Iscariot. The disciples cannot heal the young man. This may explain why the disciple in red points to Jesus on top of the mountain. The sick young man on the right has a blue cloth wrapped around his waist and looks very pale as he makes a wild gesture. You can see that his eyes look in different directions. The man behind him in the green robe is his father holding him up, looking at the disciples with hope and fear at the same time. Facing the young man, two women look at the disciples while pointing at the young man.

Both stories are described in Matthew 17, Mark 9, and Luke 9. The biblical story describes how Jesus is transfigured into radiant glory as he prays with three of his disciples on a mountain. Jesus speaks with Moses and Elijah and also hears the voice of God. The Feast of the Transfiguration is still celebrated in many churches, either on August 6 or August 19.

The dimensions of the Transfiguration are 403x276 cms. Raphael preferred to paint on canvas, but this painting was done with oil paints on wood as the chosen medium. Raphael actually showed advanced hints of mannerism and techniques of the Baroque period in this painting. The stylized, contorted poses of the figures in the lower half indicate mannerism. The dramatic tension within these figures and the liberal use of light to dark, or chiaroscuro contrasts, represent the Baroque period of exaggerated movement to produce drama, tension, exuberance, or illumination. The Transfiguration was ahead of its time, just as Raphael's death came too soon.

The Transfiguration was Raphael's last great work and an undoubted masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, it is now in the Pinacoteca Apostolica, one of the Vatican Museums. The result of a major restoration in 1977 by Vatican conservation experts, Raphael's Renaissance color palette is now fully visible and the painting has been restored to its pristine splendor. The restoration also dispelled any lingering doubts about the painting's creator. Although unfinished, this great masterpiece was entirely the product of Raphael's genius.

Buy a reproduction The Transfiguration of Raphael at the Kuadros online store

No.7 The Last Judgment - Michelangelo (1475-1564)

Kuadros takes the reader a closer look at the history of this iconic fresco to better understand how The Last Judgment has had a lasting impact on the world of religious art.

Western prophetic religions (ie, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) developed concepts of the Last Judgment that are rich in imagery.

"He will come to judge the quick and the dead" (from the Apostles' Creed, one of the earliest declarations of the Christian faith).

The Last Judgment was one of the first works of art that Paul III commissioned when he was elected to the papacy in 1534. The church he inherited was in crisis; the Sack of Rome (1527) was still a recent memory. Paul sought to address not only the many abuses that had led to the Protestant Reformation, but also to affirm the legitimacy of the Catholic Church and the orthodoxy of its doctrines (including the institution of the papacy). The visual arts would play a key role in his agenda, beginning with the message he addressed to his inner circle in commissioning The Last Judgment.

Painted when Michelangelo was fully in his mature style, the artwork had an immediate impact and sparked controversy. While this final judgment of humanity was not an unusual subject for a Renaissance artist, Michelangelo made it uniquely his own using a style that was both appreciated and despised.

This new wall of the Sistine Chapel would have a specific theme: The Last Judgment. The description of the second coming of Jesus Christ and God's final judgment on humanity was a popular theme throughout the Renaissance. Michelangelo's vision on the subject, over time, has become iconic. In the fresco, we see more than 300 figures expertly painted to carry out this story. Christ sits in the middle, his hand raised to judge the damned as they sink into the depths of hell. With rippling muscles, this Christ is an imposing figure. To his left sits the Virgin Mary. He has struck a demure pose in contrapposto and looks towards those who have been saved. Immediately around this central couple is a group of important saints. Saint Peter, who holds the keys to heaven, and Saint John the Baptist are shown on the same scale as Christ. Charon and the souls of the damned. The overall composition rotates in fluid motion, with the saved to the left of Christ in the photo rising from their graves while the damned are hurled into Hell. At the bottom of the fresco, we see Charon, a mythological figure. In Greek and Roman mythology it transported souls to the underworld. Here, he takes them straight to Hell, which is full of ghoulish characters.

Like Dante in his great epic poem, The Divine Comedy, Michelangelo sought to create an epic painting, worthy of the greatness of the moment. He used metaphors and allusions to embellish his theme. Your educated audience would delight in its visual and literary references. Originally intended for a restricted audience, reproductive prints of the fresco quickly spread it far and wide, placing it at the center of lively debates about the merits and abuses of religious art.

While some hailed this famous painting as the pinnacle of artistic achievement, others considered it the epitome of everything that could go wrong with religious art and called for its destruction. In the end, a compromise was reached. Shortly after the artist's death in 1564, Daniele Da Volterra was hired to cover bare buttocks and groin with scraps of drapery and repaint Saint Catherine of Alexandria, originally portrayed without clothes, and Saint Blaise, who loomed over her with his steel combs (how heavy!).

In contrast to its limited audience in the 16th century, thousands of tourists now watch the Last Judgment daily. However, during papal conclaves it becomes once again a powerful reminder to the College of Cardinals of their place in salvation history, as they come together to elect the earthly vicar of Christ (the next Pope), the person who will be responsible for shepherding the faithful. in the community of the elect.

Buy a reproduction of The Last Judgment by Michelangelo in the Kuadros online store

No.8 The Tower Of Babel - Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563)

According to Old Testament history, God punished humanity in three ways.

The first was the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, after Original Sin. Then came the Great Flood, the punishment for the multiplicity of human iniquities. And the third was when God, suspicious of the pride and presumption of the citizens of the violent new city of Babylon, "confounded the speech of the whole world and scattered them over the wide face of the earth."

What had the Babylonians done that was so inflammatory? In the eyes of God, they had defied the order of things with their declared desire to become a "great people", represented by the construction of a huge tower, "with a top reaching to heaven". Humans were not supposed to aspire to such lofty heights, whether physical or metaphorical. God's chosen punishment for this was to put an end to the common language that previously united all peoples, and to create a multiplicity of different languages, "so that they cannot be understood." The resulting confusion meant that "the construction of the city came to an end". According to the Bible, "that is why the city was called Babel" or Babylon. Of all the art depictions of this great tower that had so offended God, the most memorable is Pieter Bruegel the Elder's Tower of Babel (1563).

This famous painting, one of many paintings dedicated to religious art, was the second of three versions of the Tower of Babel painted by Pieter Bruegel. The first version (now lost), was an ivory miniature, which was in the inventory of the Croatian-born Italian miniaturist Giulio Clovio (1498-1578), with whom Bruegel collaborated in Rome in 1553. The third version was an oil painting. smaller painted on wood, dated 1564, now in the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. The Rotterdam painting is generally believed to date from about a year after the Vienna image. The "Great" Viennese Tower is almost twice the size of the "Little" Tower in Rotterdam and is characterized by a more traditional treatment of the subject. Based on Genesis 11:1-9, in which the Lord confuses the people who began to build "a tower whose top may reach heaven", it includes, as the other version does not, the scene of King Nimrod and his entourage. before the crowd of kneeling workers. This event is not mentioned in the Bible, but was suggested in Flavius Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews.

To Bruegel it was important because it underlined the king's sin of pride and arrogance that the image is supposed to highlight.

Detailed Realism The Tower of Babel features a great deal of meticulous detail, related to the construction of the building, enhanced, no doubt, by Bruegel's intricate knowledge of construction techniques, acquired during the execution of several paintings illustrating the excavation of the Antwerp-Brussels canal. To the right is a huge crane, very similar to the one visibly placed above the harbor in the Grimani Breviary.

The ant-like workers are busy loading it up with huge stone slabs they've received from below and will proceed to the upper ramp where others are ready to greet them. A worker climbs a ladder into that section, which is being transformed from rock into structured architecture by a multitude of other people. On the left, part of the façade is already being partly finished; a woman enters through one of the doors, a ladder appears through one of the upper windows. Higher up, another great multitude of workers works on the roof, and so on ad infinitum.

Whatever the reasonableness of these individual actions, and this point has not yet been fully investigated, the viewer immediately feels the grotesque inadequacy of the engineering means, as well as the madness of the entire construction company.

As hard-working as these 'ants' are, they face desperate odds that are brilliantly demonstrated. Within the same level, the finishing of the last detail is opposed to bare beginnings, with intermediate stages in the middle, hinting at a frantic race against inexorable time, while the upper part is still invaded by clouds.

When we look at Bruegel's painting and try to interpret it, we are also engaged in an exercise in translation: was he simply giving visual expression to the biblical story? Or was he trying to do something broader, or just a combination of both?

It should come as no surprise that there is not necessarily agreement in the art world about Bruegel's intentions. Instead of being openly controversial, the master has embedded his work with signs and leaves us, his faithful viewers, to interpret them for ourselves.

Buy a reproduction of The Tower Of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder at Kuadros online store

No.9 Virgin Of The Goldfinch - Raphael (1505-1506)

The Madonna of the Goldfinch, one of Raphael's Florentine panels, was painted by Raphael for the marriage of his friend Lorenzo Nasi and Sandra di Matteo di Giovanni Canigiani. The painting was badly damaged after the partial collapse of the Nasi house in 1547, as mentioned by Vasari. It was later probably restored by Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (Michele Tosini), a co-worker in Ghirlandaio's workshop, who was deeply influenced by Raphael.

The Child Jesus is lovingly caressing a goldfinch bird that the Baptist child has just given him. A symbol of the Passion (the goldfinch, because it feeds on thorns) is thus combined in a scene that, at a first level of meaning, can be seen simply as children playing.

Raphael absorbed the achievements of Florentine art that was at the forefront in Europe at the time. The artist was strongly influenced by the figure of Leonardo. The influence of the great artist-scientist is manifested in the beautiful Madonna del Jilguero (“Madonna del Cardellino”) (1506), recently restored (2008) in a wise and skilful way. Raphael embraces the pyramidal compositional approach, the soft low-light effects, and the emotional dialogue between the characters, revealing the elements of Leonardo's painting. Despite that, it is also clear what Raphael's personal style will be: the extreme sweetness of the faces, particularly the Madonnas, the masterful use of colours, the realistic rendering of the landscape, and the deep intimacy between the figures.

The Virgin Mary is dressed in red and blue. The red is a symbol of the passion of Christ and the blue is the symbol of the Church and of Mary. It was one of the most expensive pigments and therefore appropriate for use on an important figure such as Maria. The European goldfinch is associated with the crucifixion of Jesus. In this painting, Saint John passes the bird to Jesus as a warning of his violent death. From the book that Mary is holding, experts have identified the words “Sedes Sapientiae”. This is one of the devotional titles given to Mary and means "seat of wisdom." It highlights that Mary gave birth to Jesus (representing wisdom). When Mary is depicted in the role of the "seat of wisdom", she is usually shown sitting on a throne with Jesus on her lap. However, in this case, the rock on which Mary sits serves as the throne.

In the painting you can see several flowers. While not all flowers have been conclusively identified, many believe the flowers to be: anemones (representing Mary's pain at Jesus' passion), daisies (representing the innocence of the Christ Child), bananas (representing the way to follow Jesus) and violets. (representing humility).

In European art, the goldfinch is frequently used as a symbol. The European goldfinch, Carduelis Carduelis, has a red face and a black and white head. Hundreds of Renaissance paintings have depicted the goldfinch. The European goldfinch is often associated with the resurrection, but also with the soul, sacrifice and death. Legend has it that the goldfinch received the red spot on his head during the crucifixion of Jesus when he tried to pull a thorn from Jesus' crown, and a drop of Jesus' blood splashed on his head. In fact, the goldfinch is known to eat thistles and thorns and has therefore been associated with the crown of thorns that Jesus wore at his crucifixion.

The landscape, and especially the architectural forms it contains, reflect the influence of Flemish art, although it is still structured in the Umbrian manner. This influence was as alive in Florence as in Urbino in the second half of the Quattrocento. It is perhaps most visible in the sloping roofs and tall spiers, unusual features in a Mediterranean landscape. Michelangelo's influence is again evident in the well-structured figure of the Christ child.

This famous painting suffered serious damage at the end of the 16th century due to the collapse of the building where it was located. It suffered serious damage, including deep, long cuts that had disfigured the wooden panel. Many restorations took place over the centuries, but only thanks to the last one (carried out in 2008) did the work return to its original splendor. Therefore, the Virgin of the Goldfinch can be loved and admired again as one of the most beautiful examples of the great painter of Raphael the "Divine".

Buy a reproduction of The Virgin of the Goldfinch - Raphael in the Kuadros online store

No.10 Christ Of Saint John Of The Cross - Salvador Dali (1951)

The Christ of Saint John of the Cross was painted by the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dalí in 1951 at a time when he was emerging from the strong anti-religious atheism of his youth and re-embracing the Catholic faith.

Without a doubt, Dalí's best-known religious work is his "Christ of Saint John of the Cross", whose figure dominates the bay of Port Lligat. The painting was inspired by a drawing, preserved in the Convento de la Encarnación in Ávila, Spain, and made by Saint John of the Cross himself after having seen this vision of Christ during an ecstasy.

In Dali's painting, the people beside the ship are derived from an image by Le Nain and a drawing by Diego Velázquez for The Surrender of Breda. At the end of his studies for the Christ, Dalí wrote: "First of all, in 1950, I had a 'cosmic dream' in which I saw this image in color and that in my dream it represented the nucleus of the atom. This nucleus later acquired a metaphysical sense: I considered in 'the very unity of the universe', the Christ! Secondly, when, thanks to the instructions of Father Bruno, a Carmelite, I saw the Christ drawn by Saint John of the Cross, I worked geometrically a triangle and a circle, which aesthetically summarized all my previous experiments, and I inscribed my Christ in this triangle".

In the portrait, Salvador Dalí cleverly used two different realistic colors including blue and green to portray the amazing seascape, probably an allegory to the Sea of Galilee. The painter used a unique technique of painting the sea at eye level while the body of Christ hangs in the air from the cross. Behind the cross, the painter used charcoal black oil paint. This was to make the body of Christ the center of attention.

Dalí was able to portray the muscles of Christ in a fine tone. Other than that, he managed to paint shadows that created depth. In addition, Salvador painted distant mountains at eye level. At the bottom of the image, a lone man can be seen standing on a dock with his boat. The renowned painter was able to combine realistic colors and neat design to create a stunning surreal portrait of the religious figure.

It has been said that the original 16th-century version portrays a crucifix from the angle at which a dying person would view it when held up for veneration.

Dalí makes us see Christ and the cross from directly above and look down at the set of clouds below and the earth below. It is a heavenly perspective, in fact, that of God the Father. It is interesting that the Son, Christ, shares the same perspective as the Father: his point of view follows and continues that of the Father. The fourth gospel emphasizes that the Son proceeds from the Father and is one with him, seeing and doing whatever the Father tells him to do. In a way, the Father also offers the Son to the world to save it.

In the painting of the Christ of Saint John, the Sacred Heart of Jesus is not reflected externally, but is involved in the artistic display of a force that surpasses the ignominy of the Cross. Dalí paints a victorious Christ for us. It shows that the Christ of Saint John of the Cross defeats death through love.

In Dalí's "Christ of Saint John of the Cross", Jesus hanging on the Cross has disarmed the powers and authorities and has made them a public spectacle, triumphing over them with the power of his love on the Cross (Col. 2:15).

Thus, the Cross is the place where good defeats evil, where darkness is defeated by light, where the seed of the woman finally crushes the head of the serpent (Gn 3, 15), where the accusations against the world have been destroyed and nailed to the Cross. Above all, it is where love conquers hate and all forms of malice.

This famous work by Dalí was considered banal by a leading art critic when it was first exhibited in London. However, several years later, it was cut up by a fan while it was hanging in the Glasgow Museum, proof of the staggering opposite effect on viewers.

Various perspectives can be seen in the painting, an example of Dalí's phenomenal talent.

Given that Dalí's works are not yet in the public domain, Kuadros does not make replicas of this painter, not failing to admire him of course.

KUADROS, a famous painting on your wall.

1 comment

bobby

bellíssimo post