When we think of the 20th century, we often imagine factories, gray cities, wars, rapidly advancing technology, and a modernity that establishes itself almost violently. However, amidst that whirlwind, there was a school that dared to imagine a different future, cleaner, more harmonious, and even more human. That school was called Bauhaus, and although it lasted only fourteen years — from 1919 to 1933 — it forever changed the way we understand art, architecture, and even the everyday objects that surround us.

The Bauhaus was not simply an artistic movement. It was a way of life, a way of conceiving the world from the smallest (a spoon, a fabric, a lamp) to the largest (an entire building). That vision of totality made it a unique, unrepeatable phenomenon that we are still rediscovering today.

What is fascinating is that, unlike other styles that sought to impact with ornamentation, grandiosity, or visual rhetoric, the Bauhaus opted for the opposite: simplicity, clarity, geometric purity. If the Baroque had accustomed us to excess and Art Nouveau to flowing forms inspired by nature, the Bauhaus invited us to trust in the essential: a straight line, a perfect circle, a well-defined square could contain as much beauty as the most sophisticated flower.

The birth of a modern dream

Everything began in Weimar, in 1919, when Walter Gropius, a German architect with almost prophetic vision, decided to found a school that united art and craftsmanship. Germany had just emerged defeated from World War I, and society was seeking new ways to rebuild itself. In that climate of uncertainty, Gropius launched a manifesto that still moves us today with its clarity: the idea that architects, painters, and sculptors should work together as craftsmen to create a new world.

The name of the school was not casual. “Bauhaus” literally means “house of construction.” But more than bricks and cement, what was constructed there was a common language among disciplines. Gropius dreamed of eliminating the hierarchies that separated “high” art from “low” craftsmanship. For him, a vase, a chair, or a lamp could have the same aesthetic dignity as a marble sculpture.

That democratization of art was one of its greatest revolutions. The Bauhaus wanted beauty to reach all homes, not just palaces or museums. It was art to be lived, to be touched, to be used.

Contrasts with other movements

To understand the magnitude of its proposal, it is worth looking around. While in Paris the surrealists explored dreams and the irrational, and in Italy the futurists celebrated speed and the machine, in Germany the Bauhaus proposed something else: a rational, almost spiritual order, where form followed function.

In contrast to Art Deco, which filled the twenties with luxury and sophistication, the Bauhaus opted for humble materials: tubular steel, glass, concrete. While Parisian decorators were intent on dressing every object in glamour, the masters Germans bet on the honesty of materials. That austerity, however, was not poverty, but refined elegance.

A curious example: at the same time, many European homes had huge, heavy armchairs, with velvets and carved woods. Suddenly, Marcel Breuer appeared with his Wassily chair, made of steel tubes and leather, light as a bicycle. In the eyes of the time, it was a scandal. How could that “industrial” object compare to aristocratic furniture? And yet, today the Wassily is an icon of universal design, while those dusty armchairs remain as relics of a pompous past.

The Bauhaus spirit: between discipline and celebration

One of the most fascinating things about the Bauhaus is that, despite its image of geometric severity, within the school reigned an almost carnival spirit. The students and masters lived in community, shared meals, projects, ideas, and also unforgettable parties.

It is known that every year they organized large themed balls where masks, costumes, and experimental theater were an essential part of the experience. Oskar Schlemmer, responsible for the theater class, designed geometric costumes that turned dancers into abstract figures in motion. Sometimes, the school hallways transformed into a spectacle of lights and colors, closer to theatrical avant-garde than to a traditional academy.

This blend of rigor and play is one of the secrets of the vitality of the Bauhaus. They were not monks of geometry; they were passionate creators who believed in experimentation as a method of learning.

Characters and anecdotes

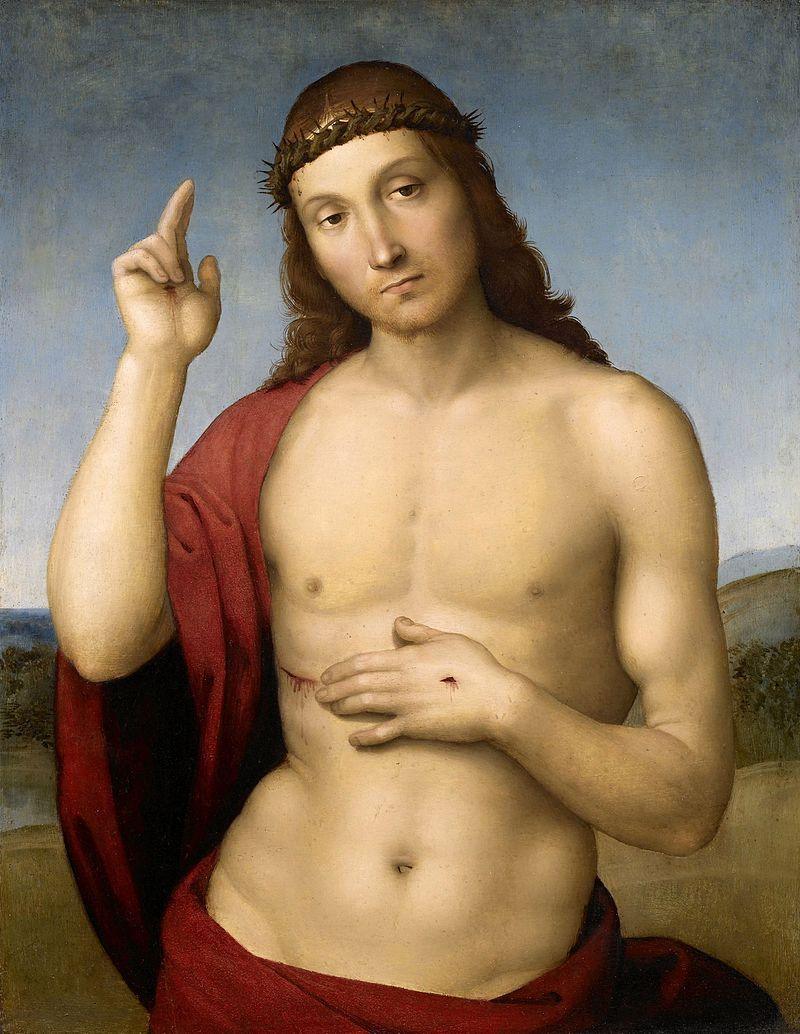

The Bauhaus brought together some of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky They gave master classes where the theory of color mixed with almost mystical reflections. Klee used to say: “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible”. That phrase became a sort of mantra for the students.

Replica of Paul Klee made by KUADROS

Josef Albers, who would later emigrate to the United States and revolutionize graphic design, was a teacher feared for his rigor but also loved for his wit. He used to conduct experiments with folded paper to teach students to “think with their hands”.

Albers - Folio of Nine Serigraphs, 1971

And then there were the women. Although the school presented itself as egalitarian, in practice many female students were relegated to the weaving workshop. However, figures like Anni Albers or Gunta Stölzl demonstrated that innovation and masterpiece creation could also happen from a loom. Today, Anni Albers' fabrics are exhibited in museums as authentic paintings abstracts.

Knotted floor rug by Gunta Stölzl

A little-known anecdote: Kandinsky, already an established painter, taught young people who saw him almost as a living myth. One day, one of them asked him if he really believed in geometry as a universal language. Kandinsky, with an ironic smile, replied: “The circle is the sun, and it can also be a fried egg. It all depends on how you look at it”. That ability to play with seriousness summarizes the spirit of the school.

The Forced Closure and the Diaspora

The Bauhaus had three locations: Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin. Each relocation was a consequence of political pressures. In Weimar, conservatives accused it of being a nest of communists and degenerates. In Dessau, it experienced its golden age with the building designed by Gropius, an architectural gem of glass and concrete. But with the rise of Nazism, the school was closed in 1933.

Far from meaning the end, the closure of the Bauhaus triggered its dispersion around the world . Many of their masters emigrated to the United States, where they founded architecture and design programs at Harvard, Yale, or Black Mountain College. Others arrived in Israel, where the "White City" of Tel Aviv became the largest urban ensemble of Bauhaus buildings on the planet. Gropius's dream, paradoxically, became global thanks to exile.

Five iconic Bauhaus works

-

The Wassily Chair (1925) by Marcel Breuer: Inspired by the structure of a bicycle, its use of tubular steel marked a before and after in furniture design.

- The Bauhaus building in Dessau (1926) by Walter Gropius: Transparent, modular, open: the architecture of the future made present.

- The textiles of Anni Albers: Abstract works in thread and wool that redefined the role of textiles in art.

- The Triadic Ballet by Oskar Schlemmer: A fantasy of geometric figures in motion, half theater, half sculpture.

- The "Homage to the Square" series by Josef Albers: Although created after the dissolution, it crystallizes the essence of Bauhaus: chromatic discipline and visual poetry.

The everyday legacy

Today, without realizing it, we live surrounded by Bauhaus. The clean typography of our computers, the minimalist lamps in our homes, the glass and steel skyscrapers that define cities: everything echoes that school. Even in fashion, the emphasis on pure lines and basic colors owes much to that heritage.

What makes the Bauhaus unique is not just its aesthetics, but its ethics: the conviction that design can improve people's lives. In times of fast consumption and disposable objects, that idea remains a compass.

To say Bauhaus is to say modernity, but also community, play, discipline, and utopia. It was a brief school, beset by politics and prejudices, but its seed germinated in every corner of the planet. Its masters and students taught us that beauty is not a luxury, but a vital necessity.

When we sit in a comfortable chair, when we appreciate the clarity of a well-designed space, we are —without knowing it— dialoguing with the Bauhaus. It is not an exaggeration to say that it changed our way of inhabiting the world.

KUADROS ©, a famous painting on your wall.

Hand-made oil painting reproductions, with the quality of professional artists and the distinctive seal of KUADROS ©.

Reproduction service of paintings with a satisfaction guarantee. If you are not completely satisfied with the replica of your painting, we will refund 100% of your money.