The beginnings of Art Nouveau

The advent of Art Nouveau - literally "New Art" - can be attributed to two distinct influences: the first was the introduction, around 1880, of the British Arts and Crafts movement, which, like Art Nouveau, was a reaction against the cluttered design and decorative art compositions of the Victorian era.

The second was the current fashion for Japanese art, in particular woodblock prints, which swept away many European artists in the 1880s and 1890s, including artists like Gustav Klimt, Emile Gallé, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Japanese woodblock prints, in particular, contained floral and bulbous shapes and "whiplash" curves, all key elements of what would eventually become Art Nouveau.

Japanese Art Nouveau - The Wave by Katsushika Hokusai

It is difficult to pinpoint the first works of art that officially launched Art Nouveau. Some argue that the stamped, flowing lines and floral backgrounds found in the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin represent the birth of Art Nouveau, or perhaps even the decorative lithographs of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, such as Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891).

However, most point to the origins of the decorative arts and, in particular, to the cover of a book by the architect and English designer Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo for the 1883 volume Wren's City Churches.

Mackmurdo, Arthur: credited as the first representation of Art Nouveau

The book's design features serpentine flower stems emanating from a flattened block at the bottom of the page, clearly reminiscent of Japanese woodblock prints.

Art Nouveau Exhibitions

Art Nouveau was often more conspicuous at international exhibitions during its peak. The new style enjoyed center stage at five particular fairs: the Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900 in Paris; the 1897 Tervuren Exhibition in Brussels, where Art Nouveau was largely employed to showcase the possibilities of craftsmanship with exotic woods from the Belgian Congo; the 1902 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts in Turin; and the 1909 International Exhibition of l'Est de la France in Nantes.

At each of these fairs, the style was dominant in terms of the decorative arts and architecture displayed, and in Turin in 1902, Art Nouveau was truly the style chosen by virtually all designers and all nations represented, excluding any other.

Poster International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art

The Art Nou veau: an art movement with a thousand names

veau: an art movement with a thousand names

Siegfried Bing, a German merchant and connoisseur of Japanese art residing in Paris, opened a store called L'Art Nouveau in December 1895, which became one of the main suppliers of the style in furniture and decorative arts. In no time, the name of the store became synonymous with the style in France, Great Britain, and the United States. However, the great popularity of Art Nouveau in Western and Central Europe meant that it had several different titles. In German-speaking countries, it was generally called Jugendstil (youth style), taken from a Munich magazine called Jugend that popularized it. Meanwhile, in Vienna, home to Gustav Klimt, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann, and the other founders of the Vienna Secession, it was known as Sezessionsstil (secession style).

It was also known as Modernismo in Spanish, Modernisme in Catalan, and Stile Floreale (floral style) or Stile Liberty in Italy, the latter due to Arthur Liberty's fabric store in London, which helped popularize the style. In France, it was commonly called Style Moderne and occasionally Style Guimard in honor of its most famous practitioner there, architect Hector Guimard, while in the Netherlands it is often referred to as Nieuwe Kunst (New Art).

It should be noted that its numerous detractors also gave it various derogatory names: Style Nouille (noodle style) in France, Paling Stijl (eel style) in Belgium, and Bandwurmstil (tapeworm style) in Germany, all names that playfully referenced the Art Nouveau trend of employing sinuous and flowing lines.

Art Nouveau: concepts, styles, and trends

The ubiquity of Art Nouveau in the late 19th century can be partially explained by the use of popular and easily reproducible forms by many artists, found in the graphic arts. In Germany, Jugendstil artists like Peter Behrens and Hermann Obrist printed their work on book covers and exhibition catalogs, magazine ads, and posters.

But this trend was by no means limited to Germany. The English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, perhaps the most controversial figure of Art Nouveau for his combination of the erotic and the macabre, created a series of posters in his brief career that employed graceful and rhythmic lines. Beardsley's highly decorative prints, such as The Peacock Skirt (1894), were both decadent and simple, and represent the most direct link we can identify between Art Nouveau and Japonism/Ukiyo-e prints.

The peacock skirt of Aubrey Beardsley - Art Nouveau

The peacock skirt of Aubrey Beardsley - Art Nouveau

In France, the posters and graphic production of Jules Chéret, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Bonnard, Victor Prouvé, Théophile Steinlen, and some others popularized the luxurious and decadent lifestyle of the belle époque, roughly the era between 1890-1914, generally associated with the sleazy cabaret district of Montmartre in northern Paris.

Their graphic works used new chromolithographic techniques to promote everything from new technologies like telephones and electric lights to bars, restaurants, nightclubs, and even individual artists, evoking the energy and vitality of modern life. In the process, they soon elevated the poster from pedestrian advertising to elevated art.

The modernist architecture of Art Nouveau

In addition to the graphic and visual arts, any serious discussion of Art Nouveau must consider the architecture and the great influence it had on European culture. In urban centers like Paris, Brussels, Glasgow, Turin, Barcelona, Antwerp, and Vienna, as well as in smaller cities like Nancy and Darmstadt, along with places in Eastern Europe like Riga, Prague, and Budapest, Art Nouveau architecture largely prevailed, both in size and appearance, and is still visible today in structures as varied as small townhouses to large institutional and commercial buildings. Especially in architecture, Art Nouveau was exhibited in a wide variety of languages.

Many buildings incorporate a prodigious use of terracotta and colorful tiles. The French ceramist Alexandre Bigot, for example, became famous largely through the production of terracotta ornaments for the facades and chimneys of Parisian residences and apartment buildings. Other Art Nouveau structures, particularly in France and Belgium, where Hector Guimard and Victor Horta were important practitioners, showcase technological possibilities with iron structures joined by glass panels.

Casa Batlló – Barcelona - Art Nouveau

In many areas of Europe, Art Nouveau residential architecture was characterized by local stone, such as yellow limestone or a rocky rural aesthetic with randomly coursed stone trim. And in several cases, a sculptural skin of white stucco was used, particularly in Art Nouveau buildings used for exhibitions, such as the pavilions of the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle and the Vienna Secession Building. Even in the United States, the vegetal forms that adorn Louis Sullivan's skyscrapers, such as the Wainwright Building and the Chicago Stock Exchange, are often counted among the best examples of the broad architectural reach of Art Nouveau.

The Arc that remains of the Chicago Stock Exchange - Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau style furniture and interior design

Like the Victorian stylistic revivals and the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau was closely associated with interior decoration at least as much as it was conspicuous in exterior facades. Like these other 19th-century styles, Art Nouveau interiors also strove to create a harmonious and coherent environment that left no surface untouched. Furniture design occupied a central place in this regard, particularly in the production of carved wood that featured sharp and irregular contours, often handmade but sometimes machine-made. Furniture makers produced pieces for every imaginable use: beds, armchairs, dining tables and chairs, cabinets, sideboards, and chandeliers. The sinuous curves of the designs often fed off the natural grain of the wood and were often permanently installed as wall panels and moldings.

In France, the leading Art Nouveau designers included Louis Majorelle, Emile Gallé, and Eugène Vallin, all based in Nancy, and Tony Selmersheim, Édouard Colonna, and Eugène Gaillard, who worked in Paris, the last two specifically for Siegfried Bing's store called L'Art Nouveau, thus giving the entire movement its most common name.

Designer furniture - Louis Majorelle Art Nouveau

In Belgium, the cervical whiplash line and more angular and reserved contours can be seen in the designs of Gustave Serrurier-Bovy and Henry van de Velde, who admired the works of English Arts & Crafts artists. The Italians Alberto Bugatti and Augustino Lauro were well known for their forays into the style there. Many of these designers moved freely between media, often making them difficult to categorize: Majorelle, for example, manufactured his own wooden furniture designs and opened a foundry,

Alberto Bugatti Furniture Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau painting and the fine arts

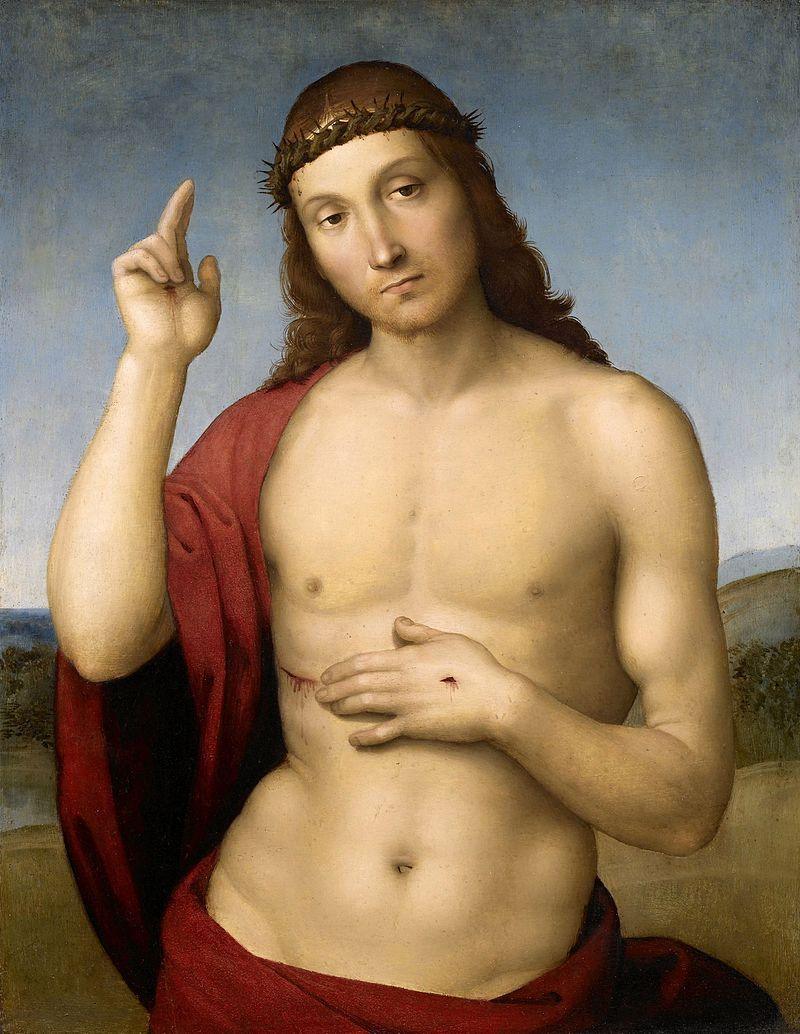

Few styles can claim to be represented in almost all visual media and materials as thoroughly as Art Nouveau. In addition to those who worked primarily in graphics, architecture, and design, Art Nouveau boasts some prominent representatives in painting, such as the Vienna secessionist Gustav Klimt, known for Hope II and The Kiss (both from 1907-08), and Victor Prouvé in France.

Hope II by Klimt - Art Nouveau

But Art Nouveau painters were few and far between: Klimt had virtually no students or followers (Egon Schiele went in the direction of expressionism), and Prouvé is equally known as a sculptor and furniture designer. Instead, it can be said that Art Nouveau was responsible, more than any other style in history, for narrowing the gap between decorative or applied arts for utilitarian objects and the fine arts or purely ornamental ones of painting, sculpture, and architecture, arts that had traditionally been considered more important, purer expressions of talent and artistic skills, whether that gap was closed completely is debatable.

Drawing by Victor Prouvé Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau jewelry and glassware

The luxurious reputation of Art Nouveau was also evident in its exploitation by some of the most well-known glass artists in history. Emile Gallé, the Daum Brothers, Tiffany, and Jacques Gruber first found fame, at least in part, through their Art Nouveau glass and its applications in many utilitarian forms. The Gallé and Daum firms established their reputations in vase designs and glass art, pioneering new techniques in acid-etched pieces whose sinuously curved and well-formed surfaces seemed to flow effortlessly between translucent tones.

The Daum brothers and Tiffany also exploited the artistic possibilities of glass for utilitarian purposes, such as lamp shades and desk utensils. Both Tiffany and Jacques Gruber, who had trained in Nancy with the Daum Brothers in jewelry, as well as René Lalique, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and Marcel Wolfers, created some of the most precious pieces of the turn of the century, producing everything from earrings to necklaces, bracelets, and brooches, thus ensuring that Art Nouveau would always be associated with end-of-century luxury, despite hopes that its ubiquity could make it universally accessible.

Corporate identity in Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau rose to fame at the same time that retail expanded to attract a truly mass audience. It occupied a prominent place in many of the major urban department stores established in the late 19th century, including La Samaritaine in Paris, Wertheim's in Berlin, and Magasins Reunis in Nancy.

Moreover, it was aggressively marketed by some of the most famous design outlets of the time, starting with Siegfried Bing's store L'Art Nouveau in Paris, which remained a bastion of style dissemination until its closure in 1905 shortly after Bing's death. His store was far from the only one in the city specializing in Art Nouveau interiors and furniture.

Meanwhile, Liberty & Co. was the leading distributor of style objects in Great Britain and Italy, where, as a result, the name Liberty became almost synonymous with the style.

Liberty & Co - Art Nouveau

Many Art Nouveau designers became famous working exclusively for these retailers before moving in other directions. Architect Peter Behrens, for example, designed practically everything from teapots to book covers, advertising posters, exhibition pavilion interiors, utensils, and furniture, and eventually became the first industrial designer when in 1907 he was in charge of all design work for AEG, the German General Electric.

The influence of Art Nouveau on culture: what came after

If Art Nouveau quickly swept through Europe in the last five years of the 19th century, artists, designers, and architects abandoned it just as quickly in the first decade of the 20th century.

Although many of its practitioners had made the doctrine "form must follow function" the center of their ethos, some designers tended to be luxurious in their use of decoration, and the style began to be criticized for being too ornate. In a sense, as the style matured, it began to revert to the same habits it had despised, and a growing number of opponents began to assert that instead of renewing design, it had simply changed the old for the superficially new. Even using new mass production methods, the intensive craftsmanship involved in much of Art Nouveau design prevented it from becoming truly accessible to a mass audience, as its proponents had initially hoped it would. In some cases, such as in Darmstadt, lax international copyright laws also prevented artists from financially benefiting from their designs.

The association of Art Nouveau with exhibitions also soon contributed to its downfall. To begin with, most fair buildings were temporary structures that were demolished immediately after the event closed. But more importantly, the exhibitions themselves, although held under the pretext of promoting education, international understanding, and peace, tended to feed rivalry and competition between nations due to the inherently comparative nature of exhibition. Many countries, including France and Belgium, regarded Art Nouveau as a potential candidate for the title of "national style," faced with accusations of foreign origins or subversive political nuances of Art Nouveau, for example in France, it was variously associated with Belgian designers and German merchants, and sometimes it was the style used in socialist buildings, turning public opinion against it. With some notable exceptions where it enjoyed a committed circle of dedicated local patrons, by 1910 Art Nouveau had almost entirely vanished from the European design landscape.

From Wiener Werkstätte to Art Deco

The decline of Art Nouveau began in Germany and Austria, where designers like Peter Behrens, Josef Hoffmann, and Koloman Moser began adopting a more sober and more severely geometric aesthetic as early as 1903. That year, many designers previously associated with the Vienna Secession founded the collective known as Wiener Werkstätte, whose preference for distinctly angular and rectilinear forms recalled a more precise, industrially inspired aesthetic that omitted any overt reference to nature.

This objectification of machine-made design qualities was underscored in 1907 by two key events: Behrens' installation as head of all corporate design for AEG, from buildings to products and advertising, making him the world's first industrial designer; and the founding of the German Werkbund, the formal alliance between industrialists and designers that increasingly sought to define a system of product types based on standardization. Combined with a new respect for classicism, and partly inspired by the 1893 Chicago World's Fair and with the official blessing of the City Beautiful movement in the United States, this machine-inspired aesthetic would eventually develop, after World War I, into the style we now call late Art Deco.

Its distinctly commercial character was expressed most succinctly at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925, the event that, in the 1960s, would give its name to Art Deco. Combined with a new respect for classicism, inspired in part by the Chicago World's Fair of 1893 and with the official blessing of the City Beautiful movement in the United States, this machine-inspired aesthetic would eventually develop, after World War I, into the style we now call late Art Deco.

Postmodern influences of Art Nouveau

Despite its brief life, Art Nouveau would be influential in the 1960s and 1970s for designers seeking to break free from the restrictive, austere, impersonal, and increasingly minimalist aesthetic that prevailed in the graphic arts. The free-flowing and uncontrolled linear qualities of Art Nouveau became an inspiration for artists like Peter Max, whose evocation of an alternative psychedelic and dreamy experience recalls the imaginative, ephemeral, and free-flowing aesthetic world of the early century.

Always recognized from the beginning as an important step in the development of modernism both in art and architecture, today Art Nouveau is understood less as a transitional bridge between artistic periods and more as an expression of the style, spirit, and intellectual thought of a certain timeframe, centered around the turn of the century, in 1900. In its quest to establish a truly modern aesthetic, Art Nouveau became the defining visual language of a fleeting moment in time.

KUADROS©, a famous painting on your wall.