The figure of Jesus is one of the most iconic in history.

The art surrounding the image of Jesus Christ has been idealized by both amateur artists and great masters.

How is it possible to depict on canvas a figure that is both completely human and completely divine? This type of artistic boldness is something even daring to attempt.

The artists who painted in the Christian tradition have done exactly that for two millennia.

The 10 Most Famous Paintings of Jesus

This is a look at the 10 most famous paintings of Jesus throughout history, according to the ranking made by experts from Kuadros.

# 1 The Last Supper - Leonardo Da Vinci

The most famous painting of Jesus Christ is undoubtedly The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci.

The work recreates the last Passover meeting between Jesus and his apostles, based on the account described in the Gospel of John, chapter 13. The artist imagined, and has managed to express, the desire that haunts the minds of the apostles to know who is betraying their Master.

Painted in the late 15th century as a mural on the walls of the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Frescoes are usually created by applying pigment to intonaco, a thin layer of wet lime plaster.

This is usually the best technique to use, as it allows the fresco to deal with the natural breathing or sweating that a wall does as moisture moves to the surface.

However, in The Last Supper, Da Vinci decided to use oil paint because this material dries much more slowly, allowing him to work on the image in a much slower and more detailed way.

Leonardo knew that the natural moisture penetrating through most stone-walled buildings would have to be sealed if he used oil paints, or the moisture would eventually ruin his work.

So the artist added a double layer of plaster, putty, and tar to combat moisture deterioration.

Despite this, the artwork has had to be restored many times in its long history.

To this day, very little remains of the initial upper layer of the oil paint as a result of environmental and also deliberate damage.

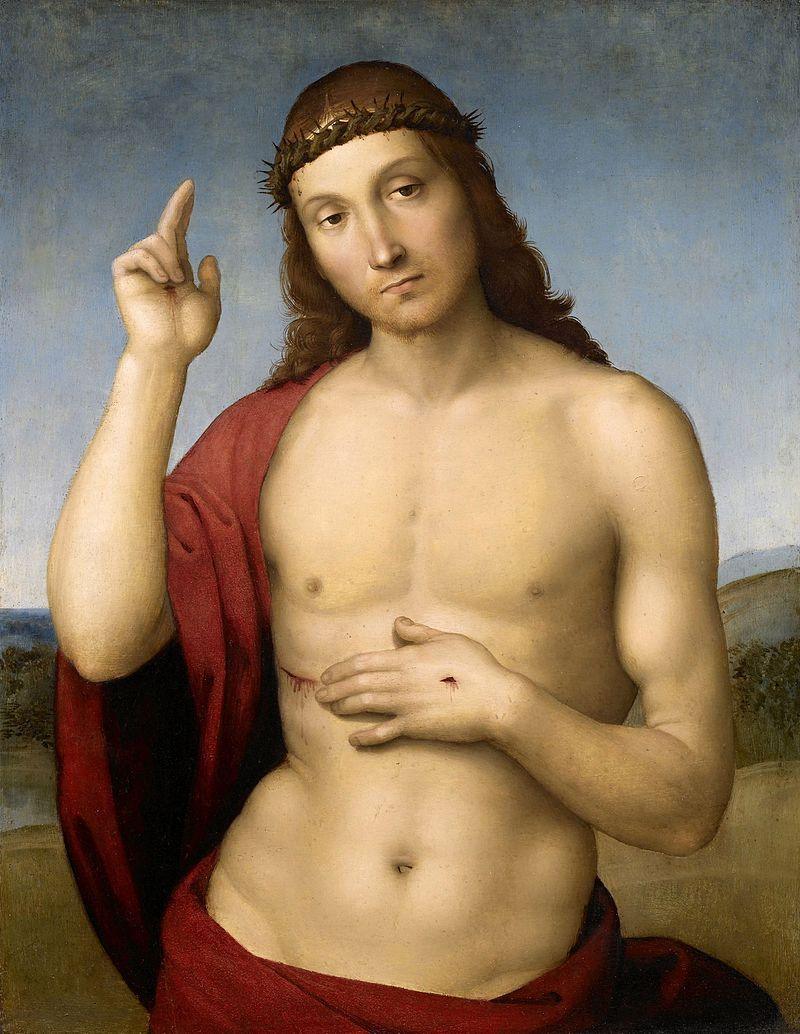

#2 The Transfiguration - Raphael

The Transfiguration by Raphael is the final work of the great Renaissance artist Raphael, commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de Medici of the Medici banking dynasty.

The artwork was originally conceived to hang as the central altarpiece of the Cathedral of Narbonne in France and now hangs in the Vatican Pinacoteca in Vatican City.

After Raphael's death, the painting was never sent to France and the Cardinal instead hung it in the main altar of the Church of Blessed Amadeus of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome in 1523.

However, in 1797 the painting was taken by French troops as part of Napoleon's Italian campaign and subsequently hung in the Louvre.

The painting can be considered to reflect a dichotomy in the simplest level: the redemptive power of Christ, symbolized by the purity and symmetry of the upper half of the painting. This contrasts with the deficiencies of Man, symbolized in the lower half by dark and chaotic scenes.

The Transfiguration relates to successive stories from the Gospel of Matthew. The upper part of the painting represents Christ elevated against undulating and illuminated clouds, with the prophets Elijah and Moses on either side of him. In the lower part of the painting, the Apostles are depicted, unsuccessfully trying to free the possessed child from demons. The upper part shows the transfigured Christ, who seems to be performing a miracle, healing the child and freeing him from evil.

The dimensions of The Transfiguration are colossal, 410 x 279 cm. Raphael preferred to paint on canvas, but this painting was made using oil paints on wood as the chosen medium. Raphael actually showed advanced indications of mannerism and techniques from the baroque period in this painting.

The stylized and contorted poses of the lower half figures indicate mannerism. The dramatic tension within these figures and the liberal use of light and dark, or chiaroscuro contrasts, represent the baroque period's exaggerated movement to produce drama, tension, exuberance, or illumination. In reality, The Transfiguration was ahead of its time, just like Raphael's death, which came too soon.

This would be Raphael's last painting, which he would work on until his death in April 1520.

The cleaning of the painting from 1972 to 1976 showed that only some of the lower left figures were completed by assistants, while most of the painting was by the artist himself.

#3 The Last Judgment - Michelangelo

The Last Judgment by Michelangelo is located on the wall behind the altar in the Sistine Chapel. Its depiction of the Second Coming of Christ in "The Last Judgment" generated immediate controversy from the Catholic Church during the Counter-Reformation.

Michelangelo was to paint the end of time, the beginning of eternity, when the mortal becomes immortal, when the chosen join Christ in his heavenly kingdom and the damned are thrown into the endless torments of hell.

No artist in 16th century Italy was better positioned for this task than Michelangelo, whose final work sealed his reputation as the greatest master of the human figure, especially the male nude. Pope Paul III was well aware of this when he accused Michelangelo of repainting the altar wall of the chapel with the Last Judgment. With its focus on the resurrection of the body, this was the perfect theme for Michelangelo.

The powerful composition centers on the dominant figure of Christ, captured at the moment before the verdict of the Last Judgment is pronounced.

His calm and imperious gesture seems to call attention and pacify the surrounding agitation. In the image begins a broad slow rotating movement in which all the figures participate. The two upper lunettes with groups of angels flying the symbols of the Passion are excluded (to the left the Cross, nails and crown of thorns; to the right the pillar of flagellation, the stairs and the lance with the sponge soaked in vinegar).

In the center of the lower section are the angels of the Apocalypse who are waking the dead with the sound of long trumpets. On the left, the resurrected are regaining their bodies as they ascend to heaven (Resurrection of the Flesh), on the right angels and demons struggle to make the damned fall into hell. Finally, in the background Charon with his oars, along with his demons, makes the damned leave his boat to lead them before the infernal judge Minos, whose body is wrapped in the spirals of the serpent.

The reference in this part to the Inferno of the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri is clear. Besides praise, the Last Judgment also provoked violent reactions among contemporaries. For example, the Master of Ceremonies Biagio da Cesena said that "it was the most dishonest thing in such an honorable place to have painted so many naked figures displaying their shame so dishonestly and that it was not a work for a Papal Chapel but for stoves and taverns" (G. Vasari, Le Vite). The controversies, which continued for years, led in 1564 to the decision of the Congregation of the Council of Trent to have some of the figures in the Judgment covered that were deemed "obscene."

The task of painting the covering curtains, known as "braghe" (pants), was entrusted to Daniele da Volterra, subsequently known as the "braghettone." Daniele's "braghe" were only the first to be made. In fact, in the coming centuries several more were added.

#4 Christ Carrying the Cross - El Greco

During his long career in Spain, El Greco created numerous paintings of Christ carrying the cross. Christ Carrying the Cross is an image of perfect humanity. The work is distinguished by the characteristic brushstrokes with which the painter uses color to model volumes and distorts bodies to reflect the spiritual yearning of the character.

El Greco paints Christ's eyes with dramatic and exaggerated tears in them. His eyes are the key element of the painting as they express a lot of emotion.

There is a delicate contrast between his robust shoulders and the feminine beauty of his hands. However, there are no signs of pain on his face. Just as his passive hands do not express anguish or effort to carry the cross.

El Greco transformed the image of Christ overwhelmed and in pain from the heavy cross to one that is calm and ready to face his destiny. The serenity of Christ in the face of his sacrifice invites the viewer to accept their own destiny in moments of fear and doubt.

#5 Christ Crucified - Diego Velázquez

This intensely powerful image of Jesus on the cross was painted during the creative period that followed Velázquez's first stimulating trip to Italy. Unlike his other male nudes that appeared in paintings like Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan and The Tunic of Joseph, his Christ on the Cross is a dead or dying body. that is not accompanied by other narrative elements except for the cross itself. Nevertheless, the artist manages to endow the work with great dignity and serenity.

The work is believed to have been a commission for the sacristy of the Convent of San Plácido, the austere posture of Christ Crucified presents four nails, the feet together and apparently supported by a small wooden ledge, allowing the arms to form a subtle curve, instead of a triangle. The head is crowned by a halo, while the face rests on the chest, allowing us to glimpse his features. His straight and smooth hair hangs over the right side of his face, his back marked by the blood dripping from the wound on his right side.

The image is unusually autobiographical in the sense that it illustrates all the major influences on Velázquez's painting. For starters, it recalls the devotional tone and iconography of the paintings absorbed during his early years in Seville under Francisco Pacheco, an active member of the Spanish Inquisition.

Secondly, it reflects his skill in figure painting acquired in Spain from studying the artists of the Spanish Renaissance and, in Italy, from the art of classical antiquity, the High Renaissance art in Rome and Venice, and the works of Caravaggio in Rome and Naples.

The influence of classicism in the work is evident in the general calm of the body and its idealized posture. The influence of Caravaggism is evident in the dramatic tenebrism that centers all attention on Christ's pale body.

It is true that the image does not have the characteristic drama of baroque painting, which is seen in religious works like The Crucifixion of Saint Peter or the Descent from the Cross. Instead, it possesses a monumental sculptural quality that elevates it, in accordance with the spirituality of the theme. The composition is absolutely simple but with a vivid contrast between the white body and the dark background, and there is naturalism in the way Christ's head falls on his chest. The tangled hair is painted with the looseness that Velázquez had seen and admired firsthand in examples of Venetian painting.

Velázquez earned a reputation as one of the best portraitists in Spain, becoming the official painter of Philip IV (who reigned from 1621 to 1640) and ultimately the greatest representative of Spanish painting of the baroque period. However, despite the fact that religious art was especially important in Spain, a country whose ruling monarchy prided itself on being one of the main patrons of Catholic Counter-Reformation art, Velázquez painted comparatively few notable religious paintings.

Instead, the artist painted the world he saw around him, specializing in portrait art, some genre painting (still lifes) and a few history paintings. Ironically, given the scarcity of his religious works, he was more influenced by the Italian genius Caravaggio, who stands out above all for his biblical art, executed in an aggressively realistic style. Velázquez was also strongly influenced by the ideas of the Italian Renaissance obtained from his Sevillian master Francisco Pacheco.

#6 Christ Carrying the Cross - Titian

Around the year 1508 or 1509, Titian painted an oil known as Christ Carrying the Cross. The true origins of the painting are somewhat mysterious, and even several art historians have occasionally attributed it to another Italian painter, Giorgione. Both painters belonged to a guild of artists connected to the school and the church, both acted in the same time and place, and it is likely that the work was painted expressly for the institution. Another mystery about the oil painting is that it was said to have miraculous healing abilities, which has been written about in many historical accounts. Pilgrims prayed in the church at a side altar where the painting hung and reported that they had been cured of ailments.

The overall mood of the work is somber and dark. The brightest colors are the muted flesh tones, and the palette is dominated by various shades of brown. Against an almost black background, Christ appears in profile carrying the cross on his shoulder. As he looks to the left, an angry-looking executioner tightens a rope around his neck, and another figure slightly behind the executioner looks inward behind the scene. The composition has a style that was innovative at the time, a close-up view that avoided perspective and depth in favor of intimacy and detail. Characteristic of Titian, the painting is filled with action and rest seems distant for the represented characters.

#7 Salvator Mundi - Leonardo Da Vinci

This famous painting, while still very appealing, is no longer considered a work by Leonardo da Vinci and lost its place among our list of the 100 most famous paintings in history.

It was originally thought that Leonardo da Vinci painted Salvator Mundi for King Louis XII of France and his consort, Anne of Brittany. Experts today question the attribution of the painting to the Italian master, despite it being sold at auction in November 2017 for $450,312,500, a record price for a work of art.

Salvator Mundi used to be part of our list of famous paintings, but it lost its place to another painting voted on by the public and our artists.

#8 The Disciples of Emmaus - Caravaggio

This work by the master Caravaggio is also known as The Pilgrimage of Our Lord to Emmaus or simply The Supper at Emmaus. The painting shows the moment when the two apostles accompanying him realize that who has been speaking to them all day has been their beloved master.

Painted at the height of the artist's fame, The Disciples of Emmaus is one of the most stunning religious paintings in the history of art. In this painting, Caravaggio brilliantly captures the dramatic climax of the moment, the exact second when the disciples suddenly understand who has been in front of them from the beginning. Their natural actions and reactions convey their dramatic astonishment: one is about to jump from his chair while the other extends his arms in a gesture of disbelief. The raw lighting underscores the intensity of the whole scene.

In the work, Caravaggio depicts the disciples as ordinary workers, with bearded, wrinkled faces and tattered clothing, in contrast to the young, clean-shaven Christ, who seems to have come from a different world.

There are some secrets hidden at various points. In the work, the artist hid an Easter egg, for example. The shadow cast by the fruit basket on the table also appears to depict a fish, which could be an allusion to the great miracle.

And there are more hidden treasures in this masterpiece. Sometimes, a defect is not a defect at all, but a stroke of genius. Take, for example, the woven texture of the wicker basket that teeters on the edge of the table in the center of the painting.

Although countless eyes have marveled at the mysterious drama unfolding in the shadowy interior of that inn, the significance of an almost imperceptible imperfection has gone unnoticed through the centuries until now.

A loose twig, protruding from the wicker weave, transforms Caravaggio's famous canvas into a bold act, a spiritual challenge for the observer.

To appreciate all the implications of this small detail, it is worth remembering the contours of the general atmosphere that Caravaggio was evoking in his work.

The theme of The Supper at Emmaus is something that has inspired great masters in history, from Rembrandt to Velázquez. The key moment is narrated in the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament. There the story is told of Christ's intimate meal with the two disciples, Luke and Cleopas, who are unaware of the true identity of their companion. In the painting, the bread has already been broken and blessed, and the moment has come, according to the Gospel account, for Christ to "open" the eyes of his followers and disappear "from their sight."

The masterpiece captures a mystical threshold between shadows and light, the magical second before Christ, who is enveloped by the silhouette of a stranger behind him, disappears from the world. In that immeasurable instant between revelation and disappearance, Caravaggio weaves his plot, the masterful encounter between two worlds.

When the truth is revealed, Christ's uncle, Cleopas, rises from his chair, seized by panic and amazement at the revelation: his elbows rising dynamically through the sleeves of his coat.

On the other side of the wicker fruit bowl, to the right, Luke opens his arms wide as if claiming the implausibility of the scene, drawing the same posture on the cross at the moment of his painful death. Meanwhile, the innkeeper remains impassive, observing without understanding as he listens to the words Christ has spoken to his astonished disciples, unable to grasp the significance of a moment that is monumental for humanity.

The Disciples of Emmaus ranks number 82 on the list of famous paintings

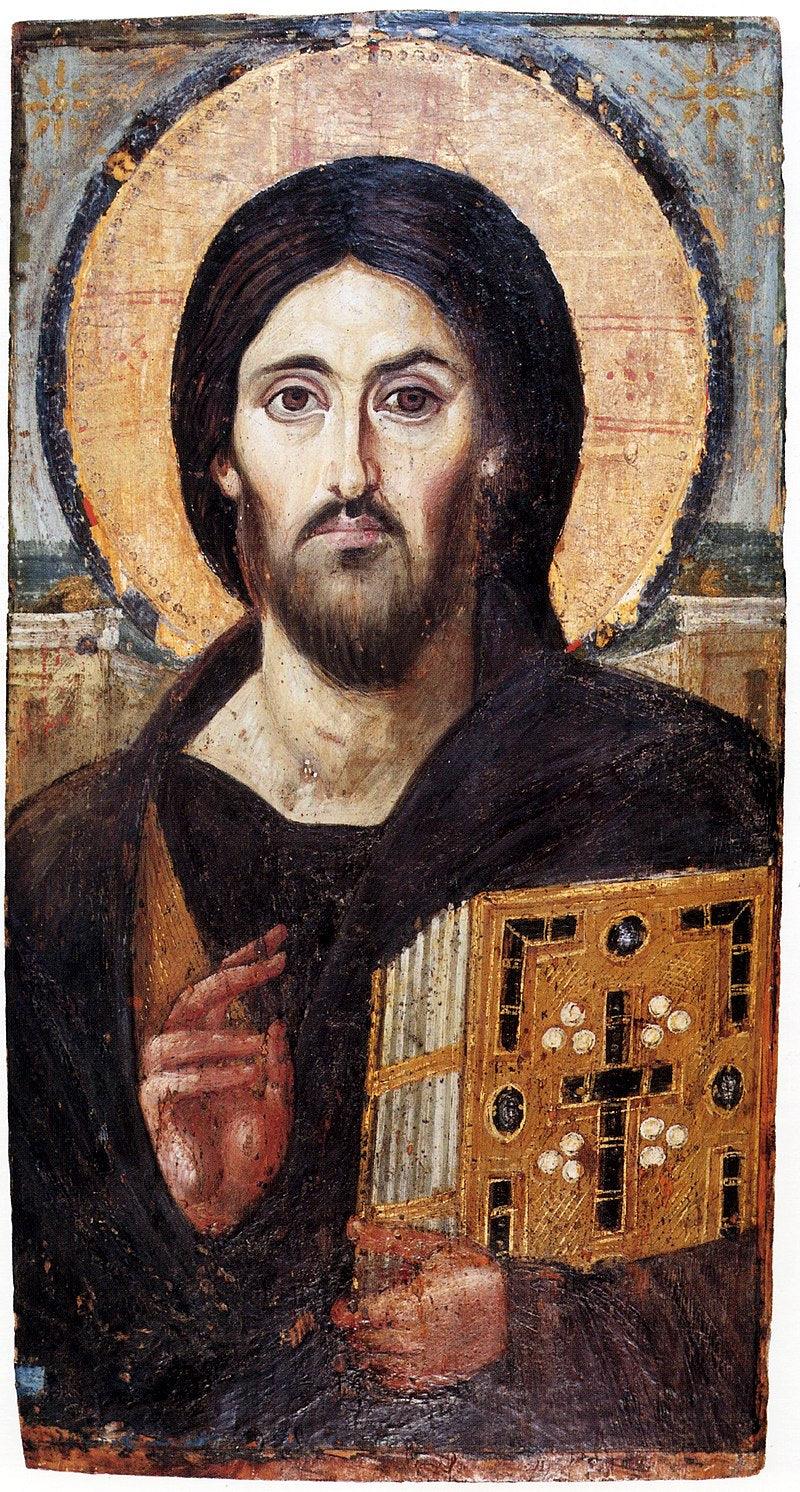

#9 Christ Pantocrator

The Christ Pantocrator is a painted wood panel dating from the 6th century from the Monastery of Saint Catherine located in Sinai, Egypt. This painting is considered one of the oldest Byzantine religious icons and is the oldest known work in the Pantocrator style.

The painted panel has a height of 84 cm with a width of 45.5 cm and a depth of 1.2 cm. It is believed that the painting was originally larger, but it was cut at the top and sides at some unknown point, to produce the current dimensions. The work shows Christ dressed in a purple robe.- a color commonly chosen to represent those of imperial status and royalty. This choice of color for his robe is a symbol of his status and importance. Christ is depicted raising his left hand in a sign of blessing and holding a book in his right.

We can assume that this book is probably a Gospel because it is adorned with jewels in the shape of a cross. The painting is deliberately asymmetrical to symbolize the dual nature of Christ. The left side of Christ symbolizes his human nature with his features represented as much softer and lighter. While the right side of Christ symbolizes his divinity with his severe gaze and intense features. The eyes themselves are different in shape and size, as well as the hair on his left side being gathered behind his shoulder.

One of the most important Christian icons is Christ Pantocrator. This image portrays Jesus as the sovereign ruler of the world. The Christ Pantocrator was one of the earliest images of Jesus and appears prominently in rock churches.

The word Pantocrator means "Almighty". In the Greek version of the Old Testament (LXX), the word pantocrator is the translation of "Lord of Hosts" and "Almighty God". In the book of Revelation, pantocrator appears nine times as a title that emphasizes the sovereignty and power of God.

The Christ Pantocrator icon emphasizes the omnipotence of Jesus, his power to do anything. Jesus is the "Ruler of All" who holds all things. The symbolism of Christ Pantocrator (explained below) is inspired by Roman imperial imagery to project his sovereign power. The early Christians used cultural symbols to proclaim the sovereign power of the risen Christ.

Additionally, the location of Christ Pantocrator in the apse (the front sanctuary wall) also has theological significance. Byzantine churches had the model of the Roman basilica, the king's chamber to hold court. The apse was the seat of authority where the ruling official sat. The positioning of Jesus in the apse declares that he is the legitimate ruler and sovereign judge over all.

Christians began to visually represent Jesus at the end of the 300s, once the threat of persecution no longer existed. These early images present Jesus as a stoic figure sitting on a throne with a scroll. By the 600s, Christ Pantocrator emerged as a simplification of that early image. The appearance of Christ Pantocrator has hardly changed in the last 1,500 years.

Most of the early images of Jesus were destroyed during the iconoclastic controversy.

#10 Christ of Saint John of the Cross

By far, the most popular of all of Dalí's religious works is undoubtedly his "Christ of Saint John of the Cross," whose figure dominates the bay of Port Lligat. The painting was inspired by a drawing, preserved in the Convent of the Incarnation in Ávila, Spain, made by Saint John of the Cross himself after having seen this vision of Christ during an ecstasy. The people next to the boat are derived from a painting by Le Nain and a drawing by Diego Velázquez for The Surrender of Breda.

At the foot of his studies for the Christ, Dalí wrote: "Firstly, in 1951, I had a cosmic dream in which I saw this image in color and which in my dream represented the nucleus of the atom. This nucleus took on a metaphysical meaning: I considered Christ as 'the very unity of the universe'! Secondly, thanks to the instructions of Father Bruno, a Carmelite, I saw Christ drawn by Saint John of the Cross, I geometrically worked out a triangle and a circle that aesthetically summarized all my previous experiments, and inscribed my Christ in this triangle".

This work was considered banal by a major art critic when it was first displayed in London.

The painting was one of the most controversial purchases made by Dr. Tom Honeyman, then Director of the Glasgow Museums. It is now widely recognized that Dr. Honeyman made a very shrewd decision when he proposed to the then Glasgow Corporation that the city purchase the painting.

Honeyman not only acquired the painting for less than the catalog price, but also bought the copyright of the work from Salvador Dalí, thus ensuring a long-term legacy from the purchase.

However, initially, the painting was not well received by all, and students from the Glasgow School of Art argued that the money could have been used to purchase works by Scottish or Glasgow artists.

After being exhibited in Kelvingrove in 1952, the Dalí attracted massive crowds.

The painting in the collection of the Glasgow Museums has not been without drama, as it has been damaged twice, most famously when the canvas was severely torn by a visitor wielding a sharp stone. The conservators at Kelvingrove managed to repair the painting to the point where the damage is now barely visible.

More than 60 years after its original purchase, the painting's enduring appeal shows no signs of diminishing and is now one of the museum's most popular exhibits.

KUADROS ©, a famous painting on your wall.

4 comments

Maria Emilia

Tremendas las pinturas bro

Maria Emilia

Tremendas las pinturas bro

JACk

This is really good information. Thank you.

Rafael Estrella Lopez

Vi una reproducción de esta obra de Dalí en el Museo de Filadelfia