Description

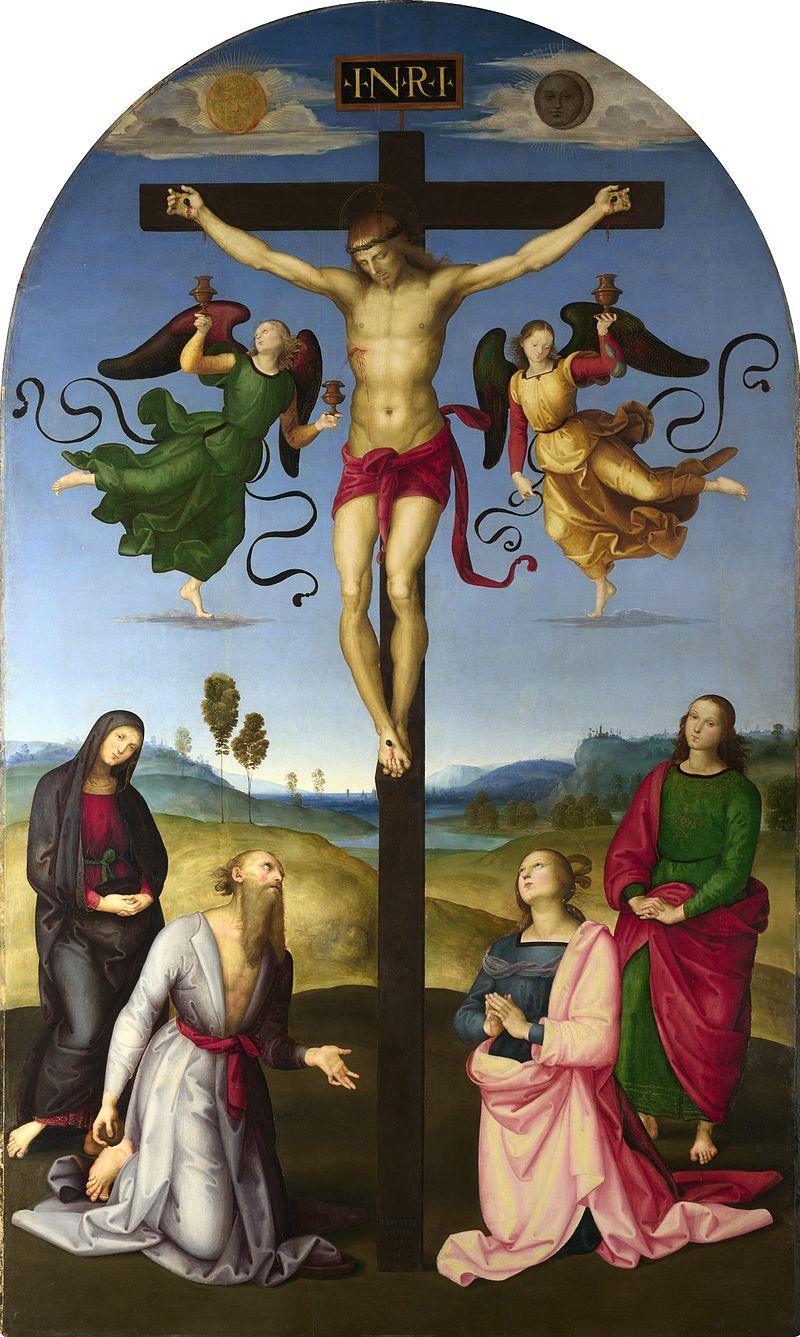

This extraordinary painting by Raphael was originally an altarpiece located in the church of San Domenico, Città di Castello, near Urbino, the artist's hometown. It shows the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist on each side of the cross. Saint Jerome and Mary Magdalene are kneeling in front of them.

One of the painter's earliest works, this altarpiece was commissioned by the wool merchant and banker Domenico Gavari for his funerary chapel dedicated to Saint Jerome.

In the work the body of Christ hangs from the cross. Two angels balance on delicate slivers of cloud on either side, collecting the blood that flows from their wounds in golden chalices reminiscent of those in which wine was served during mass on the altar below.

The sun and moon are visible in the sky, marking the eclipse that coincided with the death of Christ. Saint Jerome and Mary Magdalene are at the foot of the Cross, looking at the body of Christ with reverence and piety. The Virgin, dressed in purplish black to denote mourning, stands to the left of the Cross with John the Evangelist to the right. They both look towards the viewer and wring their hands in pain.

Art can make something terrible look beautiful. This ability can also be seen in Crucifixion Mond. The painting has minimized the pain and suffering that Christ endured on the cross. Jesus is immaculate and peaceful, except for his wounds on his feet, hands, and side. Raphael highlights the perfection of Christ in order to remain faithful to the painting style of the High Renaissance.

In the work, the atmospheric perspective plus the landscape exhibit the style of Perugini that Raphael followed. Instead of focusing on the painful and gruesome nature of Christ's death, it strengthens the doctrine of transubstantiation, serving as a symbolic blood representation for the Eucharist.

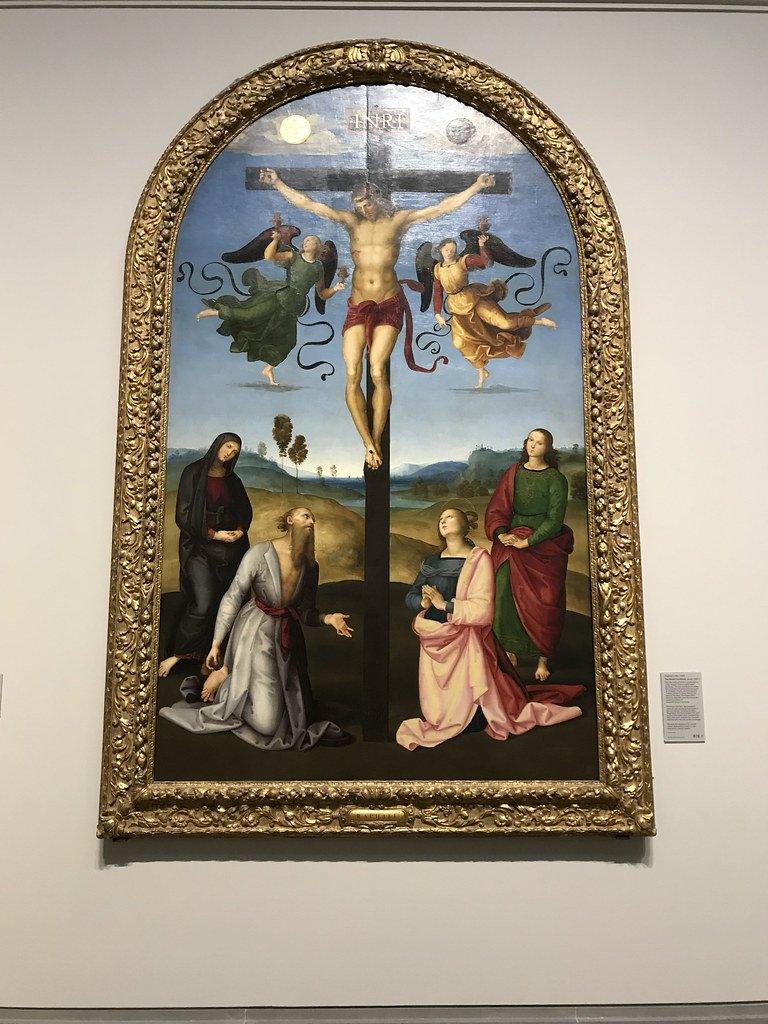

Crucifixion Mond was viewed at the London-based art museum, The National Gallery. There the typical pigments of the Renaissance period were identified.

Raphael painted his work, among other pigments, with ocher, vermilion, verdigris, lead-tin yellow and natural ultramarine. The color red has a strong meaning. Each figure in the painting has a touch of red. All the figures are pictorially touched and are redeemed by the blood of Christ.

Other colors also connect the elements of the painting in turn. There are colors in the image that have been repeated in its lower half. For example, the blue color of heaven has been picked up in the clothes worn by Saint Jerome and the green color in the clothes worn by one of the two angels is also in the clothes of Saint John.

Saint Jerome was not present at the Crucifixion but is included in this scene because the chapel was dedicated to him. He gestures towards the Cross and holds the stone with which he struck his chest while living as a hermit in the desert. Miracles that occurred after Christ's death were painted in scenes from the predella (the lower painted panel shown below the main panel of the altarpiece). Two predella panels survive in the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, and the National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon. At first, there was probably at least one additional panel. Gavari himself may have chosen to dedicate the altar to St. Jerome, since he also named his eldest son Girolamo (Jerome in Italian).

The altarpiece is heavily influenced by Perugino, the leading artist in central Italy at the time, with whom Raphael developed a close artistic relationship while living in Perugia. The overall design is based on various versions of the crucified Christ in a landscape painted by Perugino in the late 1480s and 1490s, and is especially similar to his Crucifixion altarpiece for the convent of S. Francesco al Monte in Perugia, commissioned in 1502 and completed 1506.

In that painting angels with fluttering ribbons hold chalices to collect blood from Christ's wounds, the Virgin and the Evangelist are nearly identical to Raphael's, and Mary Magdalene is in the same upside-down pose on the other side of the Cross. Raphael may have seen Perugino's works in his Perugia workshop before they were revealed. In addition to adopting the sweet, small-featured oval faces and stylized hand gestures of Perugino's figures, Raphael borrowed the principles of symmetry, harmony, and clarity of composition from Perugino's works. However, Rafael adapted them, giving them greater softness and sophistication. Here, however, it is not entirely clear who copied whose work.

In Raphael's early works he used to base his compositions on a simple geometric grid, incising the panel to help him transfer his drawing, as we can see in the Ansidei Madonna. No grid is visible in Mond's Crucifixion, although the image's strong symmetry and geometric structure suggest that Raphael may have used a similar method initially to expose his composition. He used a ruler and compass to make an incision around the Crucifix, and a compass to make an incision around the sun and moon. The way he left blank spaces for figures and made no revisions or changes while painting suggests that he was working from a carefully prepared design into a detailed drawing. During this period, Raphael frequently used dark shaded brushstrokes to reinforce areas of shadow, a technique derived from Perugino, particularly noticeable here on the draperies. Raphael also used his hands and fingers to dry and pattern the wet surface paint. Their fingerprints and palm prints are visible in the shadows of the heads, especially in Christ's hair, face and beard.

Raphael scratched the brown paint at the foot of the Cross down to a layer of silver leaf below to sign the painting: RAFAEL / VRBIN / AS /.P.[INXIT] ("Rafael de Urbino painted this"). Vasari commented that if Raphael had not signed the painting, no one would have believed that he and not Perugino had painted it.